Biography

By Anna Caldron, Carol Stabile, and Laura Strait

Hazel Dorothy Scott was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad on June 11, 1920 to parents Thomas and Alma Long Scott. Scott was surrounded by music as a young child: Alma played piano and gave lessons in their home. Scott was considered a prodigy. She had perfect pitch and by the age of four, she could play just about anything she heard.

Recognizing her daughter’s talent, Alma provided her daughter with formal training. In 1924, Alma and Hazel immigrated to New York City, to be with her father, Thomas Scott and Hazel’s grandmother, Margaret Long.1. When Hazel was eight, Alma took her to Juilliard for an audition. Although Scott was eight years below the age requirement, Alma somehow convinced a professor to listen to Hazel play. Impressed by her obvious talent, Professor Oscar Wagner offered to train her. By the age of eleven, Scott was working as a pianist herself. Actress Madeleine Lee Gilford recalled that when she took voice lessons, the rehearsal pianist was none other than Scott.2

As a teenager, Scott played with her mother’s group, Alma Long Scott’s American Creolians. Hazel Scott made one of her first major solo appearances in 1935, performing at the Roseland Ballroom on the same bill as the Count Basie Orchestra. Shortly after, she was given a 6-month radio contract at WOR and booked shows at nightclubs around the city. With a recommendation from close family friend Billie Holiday, Scott began playing regularly at Café Society by the time she was 19. When she was fifteen, Mutual Insurance signed her for six months of sustaining programs, and by the late 1940s, she was a frequent guest on variety shows like Ed Sullivan’s The Talk of the Town.3

Scott’s signature style was “swinging the classics.” She took well-known pieces by Bach, Rachmaninoff, Liszt, and other composers, then sped them up and added her own boogie-woogie style. Scott’s audiences loved her enthusiasm, talent and confidence. During her years at Café Society, Scott gained popularity and recognition. Scott became close with owner Barney Josephson, a civil rights proponent and member of the Communist Party who opposed segregation. Josephson eventually became Scott’s manager, supporting her refusal to play for segregated audiences.

Scott’s growing popularity New York in the 1940s opened up opportunities in Hollywood. Scott was a vocal critic of the racist stereotypes black performers were forced to play in motion pictures.

“From Birth of a Nation,” Hazel Scott observed, “to Gone with the Wind, from Tennessee Johnson’s to My Old Kentucky Home; from my beloved friend Bill Robinson to Butterfly McQueen; from bad to worse and from degradation to dishonor—so went the story of the Black American in Hollywood.”4

Scott took measures to ensure that she had control over how she was represented in films. For example, she had a contract stipulating that she would only play herself and never a character in a film and that she had full control over her wardrobe.

Scott made her first Hollywood appearance in Something to Shout About in 1943, and later that year she joined Lena Horne in I Dood It. These successes led to several more films including Broadway Rhythm, The Heat’s On, and Rhapsody in Blue.

But unafraid to speak up and unwilling to compromise in her on-screen appearances, Scott eventually faced consequences from Hollywood owners and producers. During production of The Heat’s On, several black women were given aprons that had been smudged with oil and dirt to wear during one of Scott’s musical numbers. Scott argued publicly with wardrobe designer on the set, David Lichine, about having black women wear dirty “Hoover” aprons and refused to show up for three days of filming. In the end, the aprons were removed altogether. Although Scott had gotten her way, she would pay for her protest. This incident was relayed to Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures, who famously said of Scott, “She will never set foot in another movie studio as long as I live.”5. Though Cohn’s prediction was not entirely accurate, the fallout from this incident marked the end of Scott’s brush with Hollywood. Disenchanted, Scott left for New York. She returned to Hollywood only briefly in 1944 to fulfill her already-contracted role in Broadway Rhythm.

- 1Karen Chilton, Hazel Scott: The Pioneering Journey of a Jazz Pianist, from Cafe Society to Hollywood to HUAC, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2010

- 2Eva LeGallienne, With a Quiet Heart: An Autobiography, New York: Viking, 1953, 111.

- 3Rob Roy, “Meet Hazel Scott, That Mystery Magnet Who Worries the Nation,” Chicago Defender, June 16, 1945.

- 4Chilton, 72.

- 5Chilton, 85.

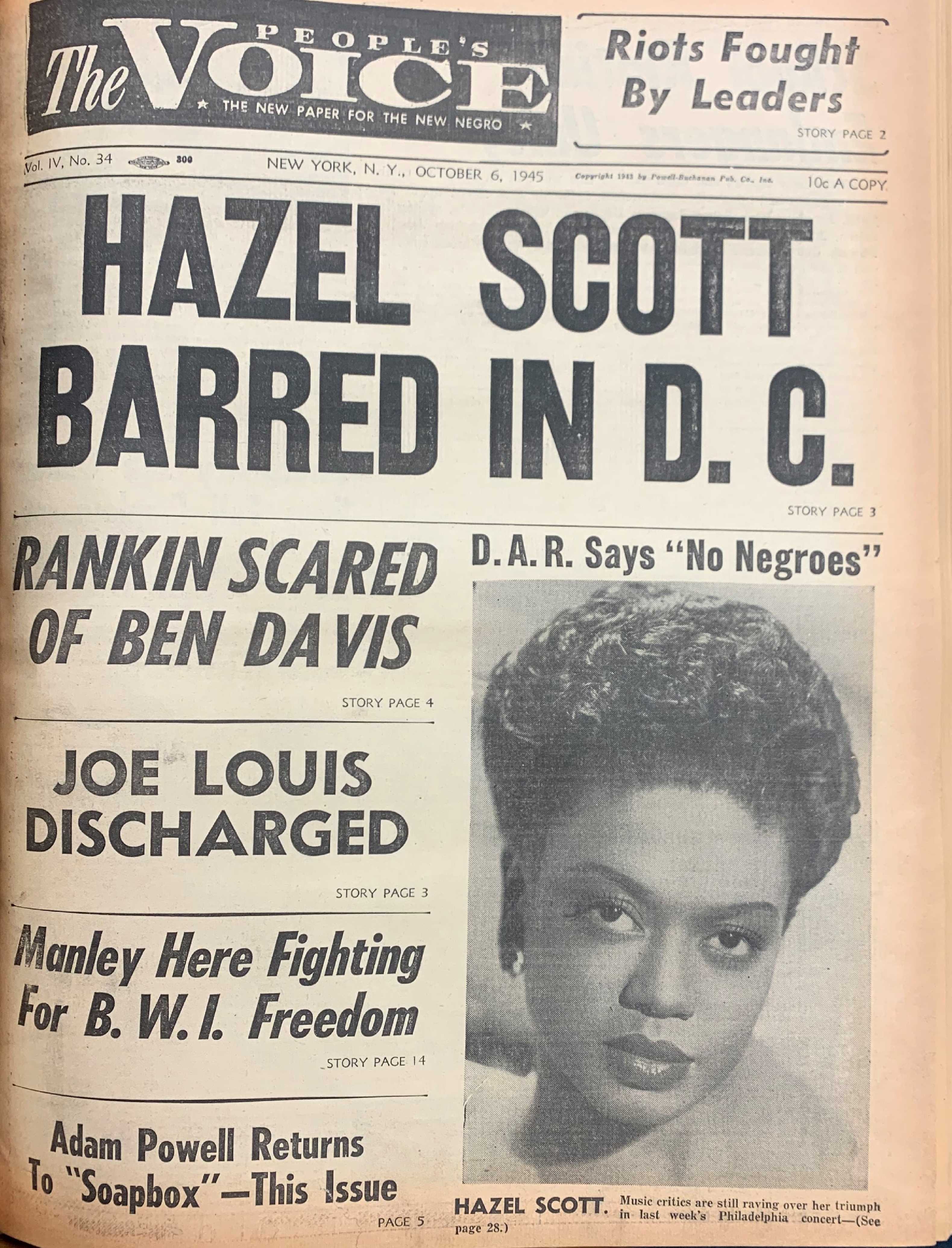

Scott continued to protest discrimination in the entertainment industry. In 1945, six years after singer Marian Anderson was prevented from appearing in the same venue, she was barred by the Daughters of the American Revolution from playing in Constitution Hall.1 In response, her husband and Harlem councilman Ben Davis wrote letters to President Truman demanding she be allowed to appear.

In 1949, Scott was traveling for work when her and Eunice Wolf, her traveling companion, were denied service at a restaurant in Pasco, Washington, the waitress told them, “because they were Negroes.”2 As Scott later told the story, she and Wolf had just gotten off a military plane (they had been performing for US servicemen in Alaska). When they were refused service, Scott told Wolf, come on, we’re going to the police station. Around the corner and up the street we went, where I looked into a pair of the coldest green eyes I have ever seen in my life and when I told what had happened he said, ‘Are you going to get out of here or am I going to run you in for disturbing the peace?’”

Scott went to her hotel room, called her agent, and said “I want the following things in the following order: a hot bath, a hot drink, and a lawyer.”3

Scott subsequently brought a racial discrimination lawsuit against the restaurant owners, who fabricated a story that Scott had demanded service “out of turn” and yelled at a waitress. According to the Spokane Daily Chronicle, a “surprise witness” testified that Scott and her friend had behaved “ladylike,” and were in fact refused service based on their race 4 Scott won $250 in damages from the suit, which she donated to the NAACP. An article in the Chicago Defender lauded Scott’s victory, calling it an “action which will redound to the benefit of all of us who are discriminated against because of our color.”5 Historian Dwayne Mack says that Scott’s victory not only helped African Americans challenge racial discrimination in Spokane, but that it inspired civil rights organizations “to pressure the Washington state legislature to enact the Public Accommodations Act” in 1953.6

Later that year, Scott became the first black woman to host her own network television show, The Hazel Scott Show. At the beginning of 1950, encouraged by Hazel Scott’s critical and commercial success on a sponsored program on WABD-TV, the upstart DuMont television network signed her to star in a new series, slated to be broadcast during prime time beginning in July 1950. The Hazel Scott Show would be the first television show to star an African American (Nat King Cole’s equally short-lived variety show did not appear until 1956). The program first aired on the DuMont Television Network on July 3, 1950, featuring Scott playing 15 minutes of whatever she pleased, always dressed elegantly and engaging and enthralling her TV audience just as she had done on stage for years. Unfortunately, the episodes of the show have all been lost to history.

As performance opportunities dwindled for her in the States following the blacklist, Scott moved to Paris in the late 1950’s. She stayed in Europe, touring and even appearing in a French film, until her return to the U.S. in 1967. Though she did perform in later years, Scott was not given nearly the same opportunity or recognition she had in the 1930s and 1940s.

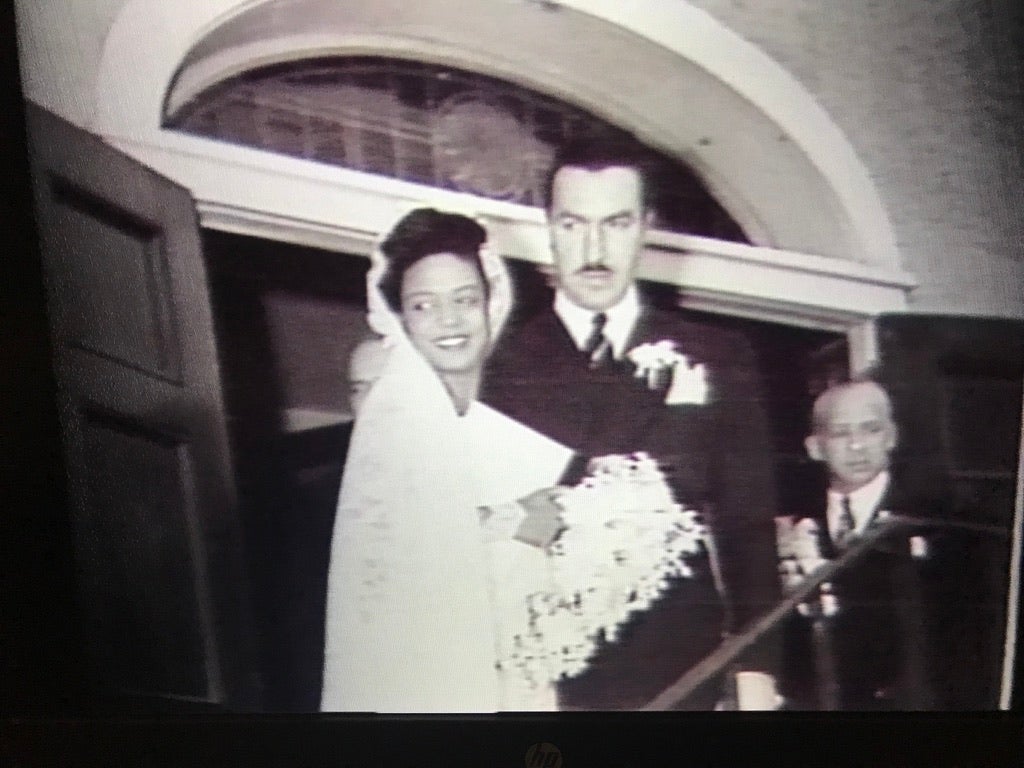

Scott married minister and U.S. Representative Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the first African American to represent New York in the U.S. House of Representatives on August 1, 1945. Scott and Powell lived in Mount Vernon, New York. They had one son, Adam Clayton Powell III, born in 1946. The couple divorced in 1960.

Hazel Scott died of cancer in 1981 at 61 years of age.

- 1“Hazel Scott Barred in D.C.,” October 6, 1945, 1.

- 2“Hazel Scott Attorneys Score in Initial Round,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, April 17, 1950.

- 3Hazel Scott Remembers, dir. Peter Pontillo, 1980 (https://www.nypl.org/research/research-catalog/bib/b11252914).

- 4“Surprise Witness Says Hazel Scott ‘Ladylike,’” Spokane Daily Chronicle, April 18, 1950, 1.

- 5“Pianist Hazel Scott Wins Round in Discrimination Suit,” Chicago Defender, January 7, 1950, 1.

- 6Dwayne Mack, “Hazel Scott: A Career Curtailed,” Journal of African American History 91, no. 2, April 1, 2006, 160.

In 1944, Hazel Scott reported to the FBI that she had received a telegram from someone purporting to be J. Edgar Hoover. The Bureau investigated this report, but when their investigation showed that she had performed at the integrated nightclub Café Society and knew its owner (Communist Party member Barney Josephson), the FBI initiated a file on Scott.

Scott’s political record also attracted anti-communist attention during the 1940s. She was a member of the Civil Rights Congress, an organization that campaigned internationally to defend African Americans convicted of crimes, especially in cases involving the death penalty; she supported the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, recognizing that the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the backlash against immigrants were part of a larger mobilization of white supremacists. Founded by the American Civil Liberties Union in 1933, the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born assisted people facing deportation, protected the rights of immigrant workers, and opposed anti-immigrant legislation.1 These and other groups were frequently identified as subversive by the FBI and anti-communists and targeted for surveillance and retaliation.

In addition to her participation in a broad range of social movements, Scott used her celebrity status to campaign against segregation. In 1945, when Scott was barred from performing in Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution (just as singer Marian Anderson had been six years earlier), she and her husband, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., made headlines with their protests.2.

Later that year, Scott refused to perform for the all-white National Press Club.3 And in early 1950, Scott filed her landmark civil rights lawsuit against the Spokane restaurant that refused to serve her and her companion.

Because of her record of progressive political activism, Scott was one of 41 women listed in Red Channels: The Report on Communist Influence in Radio and Television in June 1950. This listing threw the future of her groundbreaking The Hazel Scott Show, and Scott’s career as a whole, into jeopardy. Scott, who had never been a member of the Communist Party, sought to set the record straight by appearing voluntarily before “the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC]… to ask for the opportunity of appearing and stating her case.”4 Scott knew that the members of the HUAC, including future President Richard M. Nixon and John S. Wood—a senator from Virginia and chairman of the HUAC, who was rumored to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan—were unlikely to be sympathetic.5

- 1Rachel Ida Buff, Against the Deportation Terror: Organizing for Immigrant Rights in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2017.

- 2“Report Truman to Probe Ban Against Hazel Scott,” Chicago Defender, October 13, 1945.

- 3Venice T. Spraggs, “Hazel Scott Won’t Play for Lily-White Press Club,” Chicago Defender, November 17, 1945.

- 4“Gypsy, Scott & Wicker in Red Denials.” Billboard, September 23, 1950, 16.

- 5“Dixie Leader Says Ike Nominee a Klansman,” Jet, March 24, 1955; “High-Low Democracy,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1950.

But Scott wanted to ensure that her protest was written into the historical record. Over the objections of committee members, Scott insisted on reading her prepared speech into the record in its entirety, fervently denying that she was “ever knowingly connected with the Communist Party or any of its front organizations.” Scott also criticized Red Channels’ strategies and anti-communists’ integrity, describing herself as “one of the victims” of Red Channels’ “technique of half-truth and guilt-by-listing.” She and others, she explained, were victims of “the smear artist with a spray gun.”1 Read Hazel Scott's Testimony.

Despite these efforts, Scott’s testimony before HUAC could not save her show. The DuMont Network cancelled The Hazel Scott Show in September, just a week after Scott had appeared before the HUAC. The network fired Scott in anticipation of a protest, explaining, “It was just that we felt we could more easily sell the time if somebody else was in that spot.”2

Although the DuMont Network claimed that it could not sell air time for her show, Scott told the press, “her DuMont TV show had been building steadily, had attracted considerable sponsor interest, was right on the verge of being sold, until Red Channels became the book of the industry.”3

Like others affected by the blacklist, Scott subsequently moved to Paris in the late 1950s, where she performed frequently in France and throughout Europe. She did not return to the United States until 1967. Although she continued to work in radio and television and perform internationally, Scott never hosted her own show again. Google Drive: Read Hazel Scott's FBI Files.

- 1Hazel Scott, “Testimony of Hazel Scott,” U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Un-American Activities, Eighty-First Congress, September 22, 1950, 3619–20.

- 2Merle Miller, The Judges and the Judged: The Report on Blacklisting in Radio and Television (New York, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1952), 112.

- 3“Gypsy, Scott & Wicker in Red Denials.”

Discography

Prelude In C Sharp Minor, Op. 3, No. 2 / Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 In C Sharp Minor (1940)

Piano Greats - Andre Previn*, Earl Hines, Hazel Scott, Matt Dennis, Barkley Allen, Eddie Hazel Scott - Prelude In "C" Sharp Minor / Country Gardens (1941)

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 In "C" Sharp Minor / Valse In "D" Flat Major (1941)

Ritual Fire Dance / Two Part Invention In "A" Minor (1941)

Hazel's Boogie Woogie / Blues In B Flat (1942)

Her Second Album Of Piano Solos With Drums Acc. (1942)

People Will Say We're In Love / Honeysuckle Rose (1943)

Body And Soul / "C" Jam Blues (1943)

A Piano Recital (1946)

Great Scott! (1947)

Swinging The Classics. Swing Style Piano Solos With Drums - Volume 1 Swinging The Classics. Swing Style Piano Solos With Drums - Volume 1 (1949)

Two Toned Piano Recital (1952)

Hazel Scott's Late Show (1953)

Grand Jazz album (1954)

Relaxed Piano Moods (1955)

Discography (continued)

Round Midnight (1957)

The Man I Love / Fascinating Rhythm (1945)

I'm Glad There Is You / Take Me In Your Arms (1945)

Sonata In C Minor / Idyll (1946)

A Rainy Night In G / How High The Moon (1946)

Butterfly Kick / Ich Vil Sich Spielen (1947)

On The Sunny Side Of The Street (1947)

Take Me, Take Me / Carnaval (1957)

Hazel Scott Joue Et Chante (1957)

Im Mantel Der Nacht (1958)

Viens Danser (1958)

Le Desordre Et La Nuit (1958)

Hazel Scott (1965)

Fantasie Impromptu / Nocturne In B Flat Minor

Brown Bee Boogie

How High The Moon / I Guess I'll Have To Change My Plans

Valse In C Sharp Minor / (A) Sonata In C Minor (B) Toccata

Round, Fine And Brown / Noages

Always (1979)