Biography

By Carol A. Stabile

Lisa Sergio was a radio news broadcaster and writer. Originally a radio news broadcaster in Mussolini’s Italy, where she was known as the Golden Voice of Rome, Sergio became a leading anti-Fascist broadcaster and one of the first women to have her own radio news commentary program.

Sergio was born Elisa Maria Alice Sergio in Florence, Italy on March 17, 1905. Her mother was Margherita Fitzgerald, whose grandparents claimed to be descendants of “the Gherardini family of Florence, who immigrated to Ireland taking the name of Fitz Gerald, meaning sons of

Gherardo,” and who spent most of their time in Italy.1 Her father was Baron Agostino Sergio, a landowner. Her parents’ relationship had long been volatile, with Fitzgerald defying Sergio’s efforts to control mother and daughter. In 1910, Sergio turned violent, as his daughter later recalled,

He raised his voice, she raised hers. He dashed out of the room returning with something in his hand. She yelled, grabbed me in her arms and ran out on the terrace above the garden. The single shot missed us both by a hair. He dropped the small revolver, flew down the stairs and out of the house. I remember hearing his electric car startup and take off down the street.2

Sergio was raised by her American grandparents, who had moved to Florence. Her father died in 1916. Sergio attended the University of Florence. At the urging of her grandparents, she became an associate editor of the Italian Mail, the only English-language weekly in Italy, in 1922, when she was 17 years old. She was quickly promoted to assistant editor and then editor.[Spaulding, 61] In 1933, Sergio was invited to meet with Gaetano Polverelli, who headed Mussolini’s press office.3

From 1933 to 1937, Sergio worked as a journalist in the Italian Ministry of Popular Culture, translating official fascist speeches and policies for foreign language news broadcasts.4 Sergio gradually began to question Mussolini’s version of reality and, according to her own account, she started subtly changing the content of the speeches she was translating. When an informant prominent in the Fascist government warned her that her arrest on charges of defection was imminent, she fled Italy, with the aid of inventor and family friend Antonio Marconi.

Sergio moved to New York City and began working for NBC. At the time, radio was allowing women work in professions hitherto reserved for men. According to Stacy Spaulding, when the New York Times announced that Lisa Sergio would become a broadcaster at NBC in 1937, the paper noted that “in America for some reason or other the male species captivated the ‘mike,’” speculating about whether “the gate to the microphone will open for other female announcers”(emphasis added).5

Frustrated because she believed that "NBC was not about to allow a woman to do news," Sergio took a job at local New York City station WQXR in 1939. At WQXR Sergio became one of the first female news commentators on WQXR, developing her program, Column of the Air, which broadcast seven days a week from 1939 to 1946. In it, Sergio used her own experiences of fascism to analyze its migration to South America, to criticize the support that neutral countries were providing fascists through trade, and to convey an international perspective on the war and its aftermath.1

In 1950, Sergio emceed a 15-minute show called Stop the News, which combined news commentary on subjects like inflation and the impact of McCarthyism on foreign policy, with the quiz show format. The show was cancelled, ostensibly because the short format did not attract viewers.2

Sergio self-identified as a feminist, writing and delivering many lectures and articles on feminism and women in the years after World War II. Like other women working in media at the time, Sergio was interested in the history of women’s resistance. Sergio wrote one of the first biographies of Anita Garibaldi, partner and comrade-in-arms of Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi. Sergio also wrote a biography of Lena Madesin Phillips, a twentieth-century American feminist and early critic of the gender gap in wage equality (her biography of Lena Madesin Phillips includes a dedication to Marjory Lacey-Baker, Phillips partner for 36 years). Sergio was a supporter of progressive causes, especially civil rights. Working with Dr. Martin Luther King and civil rights activist Anna Arnold Hedgeman, Sergio helped fundraise for the 1963 March on Washington.

Sergio claimed to have been married once. In 1920, she met a man she described only as “Morris,” a member of a cavalry unit who was 18 years her senior. Although the couple wished to wed, Sergio lacked money for the dowry required for military brides. When Sergio moved to Rome, the couple lived together. Morris was diagnosed with lung cancer and the couple wed on June 14, 1931, shortly before his death. Sergio never remarried.3

Sergio was one of a tightly-knit group of women who would today be described as queer in government, publishing, and broadcasting, and her programs often featured other queer women on her shows (including Eva Le Gallienne, Margaret Webster, and Mary Margaret McBride). She had a longtime relationship with Vermont native Ann Batchelder (1885-1955), food editor at the Ladies Home Journal (Batchelder worked at the Delineator prior to that). Batchelder adopted Sergio in 1943—adoption was a strategy used by gay men in particular in the era before marriage equality to gain rights. Sergio and Batchelder are among a very few women who used this strategy. The two women divided their time between Vermont, where Batchelder had a home, and New York City. Batchelder left her estate to Sergio when she died in 1955.

Sergio died in Georgetown on June 22, 1989.

The FBI began monitoring Lisa Sergio years before her name was included in Red Channels. FBI files show that surveillance of Sergio began as soon as she arrived in the U.S., at least partly in response to claims by Italian ex-patriates that she was promoting fascist propaganda on her NBC news program.

The Bureau used a wide range of strategies to prevent Sergio from being employed. They initiated a smear campaign, claiming that Sergio had been the mistress of prominent fascist and Mussolini son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano’s mistress. In the pages of the FBI memos, the rumors escalated: in addition to sleeping with Ciano, she had slept with other prominent (if unidentified) Fascist men as well, drinking to excess and bragging about her exploits. One source quoted by the FBI said that “she advertised her bedroom experiences with Ciano” and that she “was very exhibitionistic,” whatever that meant.1 Another informant alleged she was a heavy cocaine-user, who hosted British and French intelligence officers at her apartment and had to leave because she was collaborating with them, while another claimed that German women were frequent guests to her apartment.

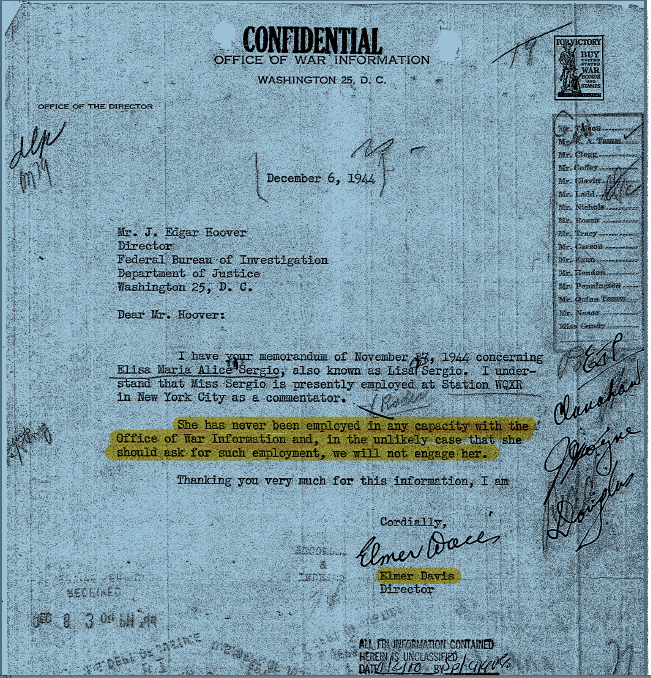

The blacklist cost Sergio more than one job. In 1943, in response to an FBI memorandum cautioning against Sergio, Elmer Davis of the Office of War Information told Hoover that

Sergio “has never been employed in any capacity with the Office of War Information and, in the unlikely case she should ask for such employment, we will not engage her.”2

After her news program was cancelled, Sergio mainly supported herself by lecturing at universities and for other organizations around the country. In 1949, the American Legion put Sergio’s name on a list of those who should not be hired for such lectures because of their Communist affiliations. In 1950, the Legion agreed to remove Sergio’s name from their list, but cautioned her that they could not “clear” her and advised her in the future to “lend your support to those organizations actively engaged in the fight against the Communist conspiracy.”3

- 1Frank L. Amprim, Rome Bureau, October 12, 1945.

- 2Letter from Elmer Davis to J. Edgar Hoover, Office of War Information, December 6, 1944, FBI #65-18966.

- 3Letter to Lisa Sergio from Henry H. Dudley, National Adjutant, the American Legion, October 24, 1950, Lisa Sergio Papers, Booth Family Collection, Georgetown University.

Despite the Legion’s assertion that she had been removed from their list, as late as 1958, the American Legion was encouraging the public to protest her appearance as a lecturer.1 Additional evidence suggests that the American Legion continued to dog Sergio’s efforts to gain employment, organizing letter-writing campaigns to prevent her from speaking on college campuses and other venues because of alleged communist ties.

Google Drive: See Lisa Sergio's FBI File.

- 1Office Memorandum from M.A. Jones to Mr. Nease, Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, April 30, 1958, FBI #65-18966.