By Carol Stabile and Jeremiah Favara

Aline MacMahon (1899-1991) was an actress who appeared on stage, television and films. MacMahon appeared in eleven television programs, thirty-two Broadway plays, and forty-three films over the course of her fifty year career. She was nominated for an Academy Award as best supporting actress in 1944 for her role in Dragon Seed.1

MacMahon was born on May 3, 1899 in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. She grew up in a family of writers. Her aunt, Sophie Irene Loeb, was a journalist for the Evening World and the founder of the Widows Pension Fund 2 Her father, William MacMahon, was a member of the New York staff of the Chicago Tribune and an Associated Press editor before becoming the editor of Munsey’s Magazine.[“Aline MacMahon Wed to Clarence S. Stein,” New York Times, March 29, 1928, 25; Lambert. Her mother, Jennie Simon MacMahon (nee Yachna Sosa Shimon), had been a child performer, who later picked up her career at the age of 53 and began acting on stage and screen.3

MacMahon moved to Brooklyn with her family as a child, where she attended Public School 103 and Erasmus High School. In her teens, she performed as an elocutionist for concerts and events for a range of religious organizations, including the Armenian Students’ Association of America in 1914. Although MacMahon was intent on pursuing a career on stage, her parents insisted that she have a college education. As MacMahon recalled years later, “to please them I went to Barnard College and had a wonder time there of course running the dramatics and acting my head off, doing all the things you can do when you’re an undergraduate and don’t get a chance to do for about ten years afterward.”4 While at Barnard College, MacMahon performed in stage productions for the college’s “Wigs and Cues,” including This Way Out, What Every Woman Knows, and Trelawney of the Wells.5

After graduating from Barnard in 1920, MacMahon debuted on Broadway in The Mirage.” Her breakthrough performance came in 1926, when she appeared in Eugene O’Neill’s Beyond the Horizon. 6 Her performance was praised by critics. Alexander Woollcott wrote she acted “with extraordinary beauty and vitality and truth.” The New Yorker said she “tempted one to rank her immediately among the Olympians,” and playwright Noel Coward described her as “astonishing, moving and beautiful.”7

These critically acclaimed performances led MacMahon to Hollywood in the early 1930s, where she continued to deliver critically acclaimed performances. Critics referred to her performance in the film adaptation of Moss Hart and George Kaufman’s Once in a Lifetime as “another feather in this actress’s cap, for so far all her film performances have elicited high praise.”8

These critically acclaimed performances led MacMahon to Hollywood in the early 1930s, where she continued to deliver critically acclaimed performances. Critics referred to her performance in the film adaptation of Moss Hart and George Kaufman’s Once in a Lifetime as “another feather in this actress’s cap, for so far all her film performances have elicited high praise.”8

- 1Bruce Lambert, “Aline L. MacMahon, 92, Actress Over 50 Years and in 43 Movies,” New York Times, October 13, 1991.

- 2Leonard Probst, “Miss Aline MacMahon: Oral Memoir,” William E. Wiener Oral History Library of the American Jewish Committee, New York Public Library, New York, New York: December 8, 1977, 3.

- 3Lambert.

- 4Probst, 5.

- 5Aline MacMahon Papers, New York Public Library.

- 6Lambert.

- 7Lambert.

- 8Mordaunt Hall, “Jack Oakie, Aline MacMahon and Others in a Film of the Hart-Kaufman Satire on Hollywood,” New York Times, October 29, 1932, 18; Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1932, 18.

Like other women of her generation, MacMahon was frustrated by the quality of the films in which she was cast. Years later, she recalled writing letters full of “gnashing of my teeth, a wailing of my . . . tearing of my hair, a wailing of my voice because the material seemed to me to be so terrible.” Conscious of the fact that during the worst years of the Depression, she was making “money to bigger money to bigger money to bigger money,” nonetheless as a self-identified “intellectual snob . . . she liked good literary material and Warner Brothers was not interested in literary material.”1 MacMahon wanted to star in smart roles, with independent women, like Edna Ferber’s Emma McChesney, which featured “a lady saleswoman. . . the first of the traveling saleswomen.” She wanted to be “a George Arliss in skirts,” a reference to the British-born actor who enjoyed unique forms of creative control, including the ability to cast actors and rewrite scripts.2

Because MacMahon wanted to spend time with her husband, she wrote her own contract, “which was three months in California, three months in the East alternately, two pictures when I was in California, nothing to do when I was in the East.” But this compromise meant that she had little control over the roles she accepted: “if they only had three months and they had to do two pictures with me, I’d have to take whatever came up.”3 But in 1933,

“enraged at the material they had given me,” MacMahon “managed to get them to cancel the contract and I went out on my own because I thought that free-lancing I would have better luck.” 4

She left Warner Brothers, she recalled years later, “because the material was so piffling” 5 Always forthright in her opinions, when Columbia’s Harry Cohn asked her how she liked a Wetern she starred in with Jimmy Stewart, MacMahon replied, “Mr. Cohn, it was distasteful, there is too much sadism in it” 6.

Despite the constraints that transformed her into a “character” actress rather than a star in her own right, MacMahon acted in numerous films in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, while continuing to perform on Broadway. She was nominated for an Academy Award for best supporting actress for her role in Dragon Seed in 1944. She also acted on television. MacMahon’s final performance was on stage in 1975, with Meryl Streep, in Trelawny of the Wells, a play she had appeared in 55 years earlier at Barnard.

MacMahon married Clarence S. Stein, an architect and urban planner, on March 27, 1928 in Manhattan. She died at age 92 at her home in Manhattan on October 12, 1991.

MacMahon did not join the Communist Party, not because she disagreed with its principles, but because the “three-months-there-and-three-months-here contract” she had negotiated in order to “come home” to New York City and “be Mrs. Stein” did not allow her the time to fully engage in Party activities.1. She and her husband believed, as MacMahon put it in an interview “that somewhere there’s going to be a rational world with enough for everybody to eat.”2. She was, she recalled, a member of

the generation who listened to Mrs. Roosevelt. She said if you blieve in something, go out and fight for it, so we were all belonging to societies and then we found ourselvles smacked in the bellies with wet fishes because a lot of people lost their livelinshoos on account of that and many of them as innocent, so to speak . . .Oh, they’re not revolutionaries, they’re just do-gooders in my book.3

MacMahon taught at the politically left-leaning Actors Laboratory Theater. She served on the Actors’ Equity Council for ten years, working on issues of economic betterment committee, pay regulations, and anti-discrimination policies.4 She was twice elected to serve as a councilor for Actors’ Equity, first in 1942 and again in 1947.5 Her nomination for councilor in 1947 was framed as part of a conflict between conservative and liberal factions in Actors’ Equity, with MacMahon squarely in the camp of alleged Communist Party members.6 The FBI considered Actors’ Equity to be a communist front organization, one that had been completely infiltrated by the Communist Party. In addition to being listed in Red Channels, MacMahon was also identified as a Communist Party member by professional informer Louis F. Budenz.

- 1Probst, 39.

- 2Ibid, 45.

- 3Probst, 47.

- 4“Equity Forms Committee on the Unemployed,” The Billboard, November 1, 1947, 46; “Equity Waives Rule on Pay for Actors,” The Billboard, May 1, 1943, 10; “Actors Condemn Detroit Riots, Send FDR Wire,” The Billboard, July 10, 1943, 14.

- 5“Three Independents Win Equity Council Posts,” The Billboard, June 14, 1947, 47.

- 6“Conservatives vs. Liberal Flare in Equity Slate,” The Billboard, April 26, 1947, 47.

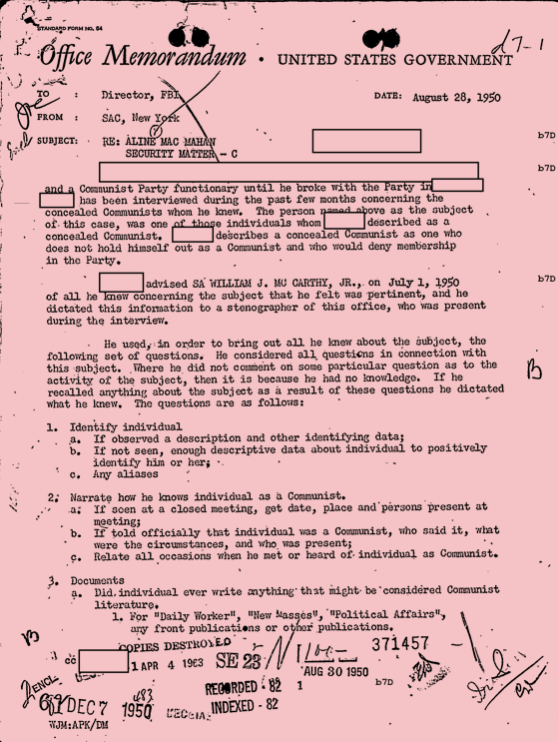

In August 1950, as a result of her being listed in Red Channels, the FBI investigated MacMahon’s background, career, travel, personal life, credit rating, etc. Subsequently, MacMahon was issued a passport restricting travel to “the British Isles, France, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and necessary countries en route.”1 Investigations into MacMahon were re-opened each time she requested a passport until 1964.

- 1SAC, WFO (100-23730), “Aline MacMahon, was. IS-R,” FBI Office Memorandum, Washington, DC: February 15, 1956, 2.

Films

Five Star Final (1931)

The Heart of New York (1932)

The Mouthpiece (1932)

Week-End Marriage (1932)

Life Begins (1932)

Once in a Lifetime (1932)

One Way Passage (1932)

Silver Dollar (1932)

Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933)

The Life of Jimmy Dolan (1933)

Heroes for Sale (1933)

The World Changes (1933)

Heat Lightning (1934)

The Merry Frinks (1934)

Side Streets (1934)

Big Hearted Herbert (1934)

Babbitt (1934)

While the Patient Slept (1935)

Mary Jane’s Pa (1935)

I Live My Life (1935)

Kind Lady (1935)

Ah Wilderness! (1935)

Where You’re in Love (1937)

Back Door to Heaven (1939)

Out of the Fog (1941)

The Lady Is Willing (1942)

Tish (1942)

Stage Door Canteen (1943)

Seeds of Freedom (1943)

Reward Unlimited (1944)

Dragon Seed (1944)

Guest in the House (1944)

The Mighty McGurk (1947)

The Search (1948)

Roseanna McCoy (1949)

The Flame and the Arrow (1950)

The Eddie Cantor Story (1953)

The Man From Laramie (1955)

Cimarron (1960)

The Young Doctors (1961)

Diamond Head (1962)

I Could Go on Singing (1963)

All the Way Home (1963)

Television

The Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse (1950)

Pulitzer Prize Playhouse (1952)

Celanese Theatre (1952)

Studio One in Hollywood (1957-1958)

Play of the Week (1959)

Lamp Unto My Feet (1961)

The Doctors and the Nurses (1964)

The Defenders (1963-1964)

NET Playhouse (1969)

Great Performances (1974)

For the Use of the Hall (1975)

Broadway

The Mirage (1920)

The Madras House (1921)

The Green Ring (1922)

The Grand Street Follies (1922)

The Exciters (1922)

The Player Queen (1923)

This Fine-Pretty World (1924)

Grant Street Follies (1924)

Artists and Models (1925-26)

Beyond the Horizon (1926-1927)

Spread Eagle (1927)

Her First Affaire (1927)

Maya (1928)

Winter Bound (1929-1930)

If Love Were All (1931)

Kindred (1939-1940)

Heavenly Express (1940)

The Eve of St. Mark (1942-1943)

The Confidential Clerk (1954)

A Day By The Sea (1955)

Pictures in the Hallway (1956)

I Knock at the Door (1957)

All the Way Home (1960-1961)

The Alchemist (1966)

Yerma (1966-1967)

The East Wind (1967)

Galileo (1967)

Tiger at the Gates (1968)

Cyrano de Bergerac (1968)

Mary Stuart (1971)

The Crucible (1972)

Trelawny of the “Wells” (1975)