Overview

The first African American woman to write and produce an opera, the only woman to head a Federal Theatre Project Unit, founder and first editor of the influential journal Freedomways, Shirley Graham (1896-1977) was a groundbreaking musician, playwright, novelist, and civil rights activist and the author of award-winning and bestselling adolescent historical fiction about people of color.

A member of the Communist Party and co-founder of the civil rights group Sojourners for Truth and Justice, Graham was blacklisted in 1950. Subsequent investigations and harassment by the Federal Bureau of Investigation of both Graham and her husband, W.E.B. Du Bois resulted in their emigration to Ghana in 1960, where she became the first woman to found a national television system.

Biography

Lola Shirley Graham was born in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1896, the daughter of Reverend David A. Graham, an African Methodist Episcopal preacher, and Etta Bell, who was half Cheyenne. Graham’s father was politically active in international struggles against colonialism and white supremacy.1 Her father was known for skillfully mediating troubled congregations and Graham spent her childhood traveling across the country, from Indiana to Louisiana to Colorado to Washington.

Years later, Graham remembered the house she grew up in as a vibrant intellectual space, where her father read Charles Dickens, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Crisis aloud to his children and where organizing against white supremacy was an integral part of everyday life.2

In June 1914, Graham graduated from Lewis and Clark High School in Spokane, Washington. She worked at a naval yard and at a movie house, where she played the organ and sang between reels.3 She met Shadrach T. McCants, her first husband, while living in Seattle. Their son Robert was born in 1923, followed by David in 1925. Graham filed for a divorce from McCants in 1925 in Portland, Oregon.

Education

After her divorce, Graham divided her time between Paris, France (where she studied music composition at the Sorbonne) and the United States, where she took classes at the Howard University School of Music (1927-28) and the Institute of Musical Arts in New York City (1929). Graham returned to the US in 1931 to attend Oberlin College, graduating in 1935 with Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in music. In 1938, Graham took courses on public relations at the Yale School of Drama and worked with NBC on radio technique. She took additional courses on public relations at Yale in 1943.4 Graham attended graduate school at New York University in the early 1940s, writing a paper on “West-African Survivals in the Vocabulary of Gullah” and completing substantial portions of a thesis on “Sociological Implications of the Flowering of Negro Literature in the Period between the Two World Wars.”

Career

In 1936, Graham moved to Chicago where she and her brother Bill formed a talent agency to represent and support African American artists. That same year, Hallie Flanagan appointed Graham director of the Chicago Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project, part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration.

- 1Gerald Horne, Race Woman: The Lives of Shirley Graham Du Bois (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 39.

- 2Graham Du Bois, “Oral History Interview with Mrs. Shirley Graham Du Bois,” January 7, 1971, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 1, Folder 1, 12.

- 3Horne, 47.

- 4Transcript, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 3, Folder 3, 28 July 1943.

After the Federal Theatre Project was shut down by anti-communists in 1939, Graham worked as a program director for the YWCA in Indianapolis. In 1941, Graham took a position as the director of Negro work with the YWCA-USO at Fort Huachuca in Arizona. In 1941, Fort Huachuca was the base of the 93rd Division, the largest Negro Division in the US army, comprised of nearly 30,000 soldiers. Graham established courses on journalism and photography for the men and their wives, starting a literary magazine edited and run by the men themselves, and trying to provide productive forms of recreation for men living in a segregated town, in a segregated military.5 She held that position until 1943, when anti-communist pressures caused the YWCA to request her re-assignment. Graham resigned instead.

After the war, Graham began publishing adolescent fiction, a profession allowing her to pursue her interest in making sure that children and young adults could find books recounting the heroism of people of color and their roles in making history. She also intensified her political commitment to civil rights (see section on “Blacklist” below).

Graham married W.E.B. Du Bois in 1951. In 1961, they emigrated to Ghana, where they received citizenship. In 1967, Graham was forced to leave after a military-led coup d'état. She moved to Cairo, Egypt, where she continued writing. Her son David Graham Du Bois accompanied her and worked as a journalist.

Shirley Graham Du Bois died on March 27, 1977, aged 80, in Beijing, China, where she had sought treatment for breast cancer.6

In his autobiography, actor, singer, and activist Harry Belafonte recalled, “The witch hunters were racists, working two campaigns as one.”1 From the perspective of anti-communists, “Negroes are worse than Communists.”2

The anti-communist attack on Shirley Graham bears that out. In 1936, when Hallie Flanagan hired Graham to head the Chicago Negro Unit, anti-communists began a public crusade to shut down the Federal Theatre Project (FTP). One Republican congressman warned of the dangers of allowing Flanagan, “a woman infatuated both by the Russian theatre and the U.S.S.R.,” to spend government funding on the arts.3 Consequently, the Federal Theatre Project’s funding was cut by a quarter in June 1937.

The debate about cutting funding to the Federal Theatre Project on the floor of Congress closely hewed to the anti-communist rhetoric of white supremacists like Elizabeth Dilling. Although the Congressional debate began by identifying communist themes and personnel in the FTP, it quickly devolved into a referendum about race relations and miscegenation. Senator Robert Rice Reynolds of North Carolina, a Nazi defender who published a prominent anti-Semitic newspaper along with a colleague (notorious fascist Gerald L.K. Smith) led the charge. In a lengthy diatribe about the sins of the Federal Theatre Project, Senator Reynolds told the story of actress Sallie Saunders, a “girl who refused to go out with a Negro” and was told by her female supervisor that “the Negro was entitled just as much to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as was the girl.” Federal Theatre Project employees, Saunders complained, “hobnob indiscriminately with them,” referring to African Americans. “Do you think,” Senator Reynolds asked, “American taxpayers would approve of our financing . . . her pursuit of happiness with whatever men of whatever color she might choose, under whatever condition and in whichever gutter might please her?”4

In 1939, all funding for the FTP was eliminated because of continued objections to its politics.

Graham worked briefly at the Phillis Wheatley YWCA in Indianapolis as director of adult activities, where she hoped to create an adult theater program. The YWCA was another target of anti-communist mobilization. In 1934, even before the YWCA spoke out in favor of a federal anti-lynching law, white supremacist and prominent anti-communist Elizabeth Dilling suggested that the “C” in the acronym stood for communist rather than Christian, further complaining that the only songs in a songbook issued by the YWCA that mentioned the word “god” were “two Negro spirituals.”5 White supremacists further considered the YWCA to be “an institution that advocates ‘intermarriage’ and the ‘intermingling’ of the races.” In a confrontation with the director of the Phillis Wheatley YWCA several years later, Dilling linked the YWCA (along with the NAACP and the Urban League) with subversion: all were “Communist-front organizations controlled by Jews.”6

And by the mid-1940s, Graham was a member of the Communist Party. In 1944, Graham’s elder son Robert had been drafted, reporting to an army induction center in Indiana. Weeks he reported, Robert called Graham from an Indianapolis hospital. After suffering a hemorrhage during training, Robert had been dismissed as being “unfit,” he told her. Graham immediately arranged to have him transported by train to New York City, where “It took several days to find a hospital . . . that would accept him.” Refused treatment at a whites-only military hospital, he was moved to another facility where, according to Graham, he died as a result of the inferior medical care he received there. Graham described this as “the greatest tragedy of my life.”7

This tragedy was a political turning point for her. “All that I could see swarming about me,” she wrote after Robert’s death, “were the disembodied white faces of the Army which had finally tossed my child out as just ‘another unfit n****r’ and those hospital attendants who left my dying son lying on the floor, refusing him a bed.”8

By the end of World War II, Graham had reached a turning point and in the years after the war, she devoted her considerable energies to three projects: writing adolescent fiction about people of color who had, like herself, made history; organizing around a series of high-profile civil rights cases, and supporting and defending an increasingly embattled W.E.B. Du Bois. Graham was on the front lines of a wide range of political battles in the 1950s, particularly those involving death penalty cases: she protested the death sentence and subsequent execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and was one of their children’s trustees. She protested the death sentences meted out to the Martinsville Seven (seven African-American men who were eventually convicted and executed for raping a white woman in Virginia). And she organized in support of Rosa Lee Ingram, an African American widow who had been sentenced to death for killing a white tenant farmer in self-defense. She was a co-founder of the civil rights group Sojourners for Truth and Justice, served on committees to defend Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and was a trustee for their young children, and was a founder of the leading African American journal, Freedomways, and its first general editor.

Graham later observed that she was an unlikely target of the broadcast blacklist. Mimicking the language of the blacklist, she wrote to a correspondent, “I am not now and never have been employed in the radio and television fields.” She had had experience in radio, researching audiences with NBC while she attended graduate school at Yale in the 1930s. Tom-Tom and her play Track Thirteen had been broadcast on NBC radio, CBS had broadcast two of her teleplays (on George Washington Carver and Phillis Wheatley), and in the late 1940s there were rumors that Graham was exploring the possibility of heading CBS’s documentary unit. Still, Graham’s successes had been in the area of book publishing not broadcasting. That the American Business Consultants would list her in a volume aimed at eradicating the red menace from broadcasting shows the preventive nature of the broadcast blacklist. It shows that the intent of anti-communists was to eliminate progressive influences while at the same time preventing progressives working in other areas of the media from ever working in the new medium of television.

Anti-Communists had many reasons for singling out Shirley Graham. She was African American, she was a member of the Communist Party, she had a longstanding association with integrated organizations considered to be communist fronts (the Federal Theatre Project, the YWCA, the NAACP) and her novels were becoming increasingly popular. In fact, two of her books had already been adapted for television. Like Jean Muir and Hazel Scott, Graham also had a prominent husband: she married internationally renowned sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois in 1951.

Graham had been the subject of anti-communist criticism in the pages of CounterAttack, dating back to a 1949 article that objected to CBS’s broadcast of The Story of Phillis Wheatley. But the publication of Red Channels served as a lightning rod that attracted renewed anti-communist attention to her work. Although the FBI’s 1950 report on Graham’s activities does not cite Red Channels as its source, the list of activities it includes is identical to that which appeared earlier in June that year in Red Channels, down to the identification of Graham as a poet. Unlike Red Channels, the FBI’s confidential documents were less circumspect about race, specifically identifying Graham as a “Negro poet, writer – female.”9

It’s hard to pinpoint when the FBI first began monitoring Graham, since the FBI listed her under numerous names, including Lola Graham Du Bois, Mrs. William Edward Burghardt Dubois, Shirley McCann, Mrs. Shadrach T. McCanns, Lola McCanns, and Shirley Graham, a proliferation of “aliases” that emphasized subversive behavior.10 The FBI began maintaining a file on “Shirley Graham Du Bois” when she married W.E.B. Du Bois in 1951. FBI monitoring of Graham’s activities intensified in the period immediately following June 1950 and the beginning of the Korean War. According to a memorandum from the Special Agent in Charge of the FBI’s New York office, on 29 June 1950, just over a week after Red Channels was published, professional informant Louis Budenz advised the FBI that although he had never met “Miss Graham,” he “received information of her being a Communist of several years and specifically around 1944 and 1945 from JACK STACHEL [a high-ranking CPUSA member]. She was represented to me as a staunch member of the Communist Party.”11 On 3 October 1950, J. Edgar Hoover advised the New York City field office “to conduct an appropriate investigation of this subject in order to determine if her name should be included in the Security Index.”12

- 1Harry Belafonte and Michael Schnayerson, My Song: A Memoir, New York: Knopf, 2011, 117.

- 2Letter from William Patterson, Civil Rights Congress to Albert Maltz, Albert Maltz Papers, Box 43, “Loose Correspondence, 1955-1957, 4 November 1955).

- 3Rebecca Sklaroff, Black Culture and the New Deal: The Quest for Civil Rights in the Roosevelt Era, Chapel Hill, UNC Press, 2009, 62.

- 4Congressional Record, 28 June 1939, Volume 84, 8133-8182.

- 5Dilling, The Red Network: A "Who's Who" and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots, Chicago: 250-1.

- 6Elizabeth Dilling Spreads Negro Hate Theories,” Chicago Defender, March 4, 1944, 10.

- 7Horne, 2000, 26.

- 8Graham Du Bois, “Oral History Interview with Mrs. Shirley Graham Du Bois,” January 7, 1971, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 1, Folder 1, 56.

- 9SAC, New York to Director, FBI, FBI Memorandum, October 3, 1950, FBI #100-370965.

- 10FBI Report, May 17, 1965, FBI #100-370965-62.

- 11Re: Shirley Graham Security Matter – C, Office Memorandum from Special Agent in Charge (NYC) to FBI Director, 8 August 1950, 4.

- 12Memorandum, FBI Director to Special Agent in Charge (NYC), 3 October 1950, 1.

The FBI’s initial investigation of Shirley Graham cited a range of anti-communist sources: CounterAttack, the House Un-American Committee’s report on the Waldorf Peace conference Graham had helped to organize in 1949, an American Legion Summary that listed Graham’s name in 1949, as well as Graham’s participation in a 1950 May Day Parade, listed as “Personally Observed” by a redacted source.13 FBI records show that Graham’s novels concerned the FBI and its anti-communists allies. Frequent references to Graham’s novels about Paul Robeson and Frederick Douglass appear in FBI reports throughout the 1950s, as in the following excerpt from a 70-page FBI “synopsis,” shows:

[Shirley Graham] is best known for her biographies of famous Negroes, written for young people. She is co-author of the book, “Dr George Washington Carver: Scientist” (1944), written for teen-age readers. Her second biography for young people, “Paul Robeson, Citizen of the World,” was published in 1946. Scheduled for early 1947 publication, was her next book, “There Was Once a Slave.”1

One FBI summary of Graham’s activities cited a letter received by J. Edgar Hoover from a confidential informant, who complained that “Paul Robeson, Citizen of the World, by Shirley Graham” was a book not “fit for formative young minds."15

Graham’s access to what one FBI special agent in charge referred to as “the subversive press” also alarmed the FBI. A report from the FBI’s New York City Red Squad urged caution in approaching Graham herself, because “the subject is an Editor of a Communist Publication and she is a lecturer and writer of Communist propaganda having access to publication in both Domestic and Foreign Communist publications.”16 For the FBI, “the thought of them [communists] taking advantage of the moment to play a role in the movement, recruit and help to blare headlines abroad trumpeting Jim Crow, was of grave concern.”17 Graham’s ideas were especially dangerous according to anti-communists because she had access to national and international distribution networks that could not be easily influenced by the FBI. Ultimately, Shirley Graham Du Bois’s FBI file amounted to over 2,000 pages (not counting the tens of thousands of pages the FBI amassed on her husband).

Because Shirley Graham was one of a few who were blacklisted who spoke candidly about their experiences, we have her account of its impact on her career. In 1951, Joseph Goldstein, editor of the Yale Law Journal, wrote to people listed in Red Channels, asking them to answer five questions about the effects of the blacklist on their careers. A few weeks later, Elmer Rice, Chairman of the Committee on Blacklisting established by the Authors League of America, sent a similar questionnaire. Graham immediately responded to both letters. Fresh from W.E.B. Du Bois’ indictment under the Foreign Agent’s Registration Act and trial (which was finally dismissed by a federal judge for lack of evidence), Graham’s response was detailed, painting a picture of widespread, organized political repression. Graham described the multiple venues through which the blacklist operated: “As an author it is extremely difficult to put one’s finger on such things as ‘denial of employment’ and the like. Books can be attacked through distribution channels, publicity, handling in stores. My income has steadily decreased.”18

Graham also told Goldstein inclusion of her name in Red Channels had resulted in demands “that my books be withdrawn from the schools and libraries” of Scarsdale, New York.19 Calls to ban Graham’s books from public libraries also followed from upstate New York, home of the American Business Consultants, as well as Wheeling, West Virginia, where Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy had made his infamous speech about Communist infiltration of the US government just six months before. In addition, publicity appearances for her most recent novel about surveyor and mathematician Benjamin Banneker, Your Most Humble Servant, were cancelled without explanation, never to be rescheduled.

Although Red Channels purported to focus on the communist take-over of the airwaves, its effects rippled across media industries. Graham’s novel about journalist and abolitionist Anne Newport Royall, for example, had received enthusiastic reviews from readers, but five major publishing houses rejected it. As Graham put it in her letter to Goldstein, “No publisher has criticized the manuscript as a piece of writing. This we could understand and accept. Novels are always worked on after being accepted by some publisher. But these refusals have each time been vague and in certain cases obviously reluctant.”20 Letters Graham received from publishers rejecting the novel bear this out. Lacking any specific criticism of the manuscript, these letters were typical of the vaguely worded rejections those who were blacklisted encountered. The novel was never published.

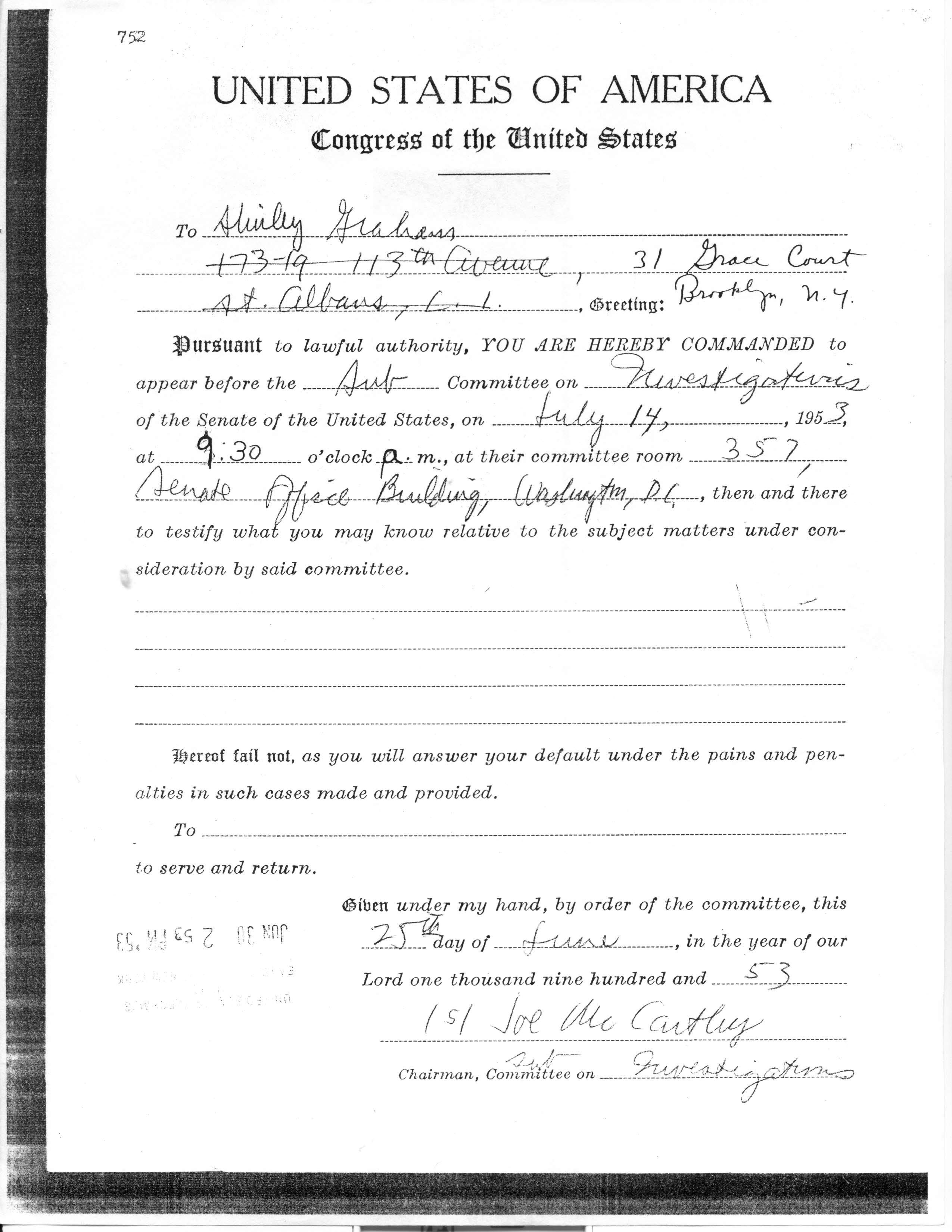

Worse was to come during the 1950s, as the FBI, the INS, and the State Department intensified their harassment campaigns against Graham and Du Bois. Du Bois was listed in the FBI’s Security Index and his file flagged as “detcom,” a reference to the list of political dissidents who were to be rounded up and taken to detention centers in the event of a national security emergency. Shirley Graham’s son David was denied a passport because of her activities. On 25 June 1953, Graham received a subpoena from the Committee on Investigations signed by Joseph McCarthy for her to appear on 15 July 1953.21

To add to this climate of fear and surveillance, the FBI cultivated the couples’ friends and employees as potential confidential informants. Some, like Harry Belafonte, refused to cooperate. Others did. As Graham put it in a letter to a friend, “None of us can come to you as I did five years ago. McCarthy’s hound dogs snarl at our heels, prowl about our doors and sniff at our windows.”22

Unemployable, their movements and activities scrutinized by the FBI, their mail constantly tampered with, suspicious of even those close to them, and with the elderly Du Bois’ health failing, the couple moved to Ghana in 1961 after W.E.B. was finally issued a passport. Few of those caught in the crosshairs of Red Channels directly defied white supremacy and capitalism in the ways that Graham did. She paid a heavy price for her activism: unemployment, government surveillance, exile, and ultimately erasure from the very history she had fought to establish.

See Shirley Graham Du Bois's FBI files at Professor William Maxwell's F.B. Eyes Digital Archive.

- 13Memorandum -- enclosure, FBI Director to Special Agent in Charge (NYC), 3 October 1950, 3-4.

- 1FBI Report, 16 May 1956.

- 15Memorandum, Special Agent in Charge (NYC) to FBI Director, 14 June 1961, 11.

- 16FBI Report, 19 June 1961.

- 17Gerald Horne, The Red and the Black: The Communist Party and African-Americans in Historical Perspective, New York: The Monthly Review Press, 1993, 226.

- 18Letter to Elmer Rice,Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 17, Folder 9, 30 January 1952, 2.

- 19Letter to Mr. Joseph Goldstein, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 17, Folder 5, 22 December 1951, 1.

- 20Letter to Mr. Joseph Goldstein, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 17, Folder 5, 22 December 1951, 2.

- 21Subpoena from the Committee on Investigations (signed by McCarthy), Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 17, Folder 10, 25 June 1953 (for an appearance on 14 July 1953). There is no evidence that Graham appeared before HUAC.

- 22Letter to Martin Anderson Nexo, Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers, Box 17, Folder 14, 5 June 1954.

Du Bois, Shirley. 1978. Du Bois: A Pictorial Biography. 1st ed. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company.

Du Bois, Shirley Graham. 1954. “As a Man Thinketh in His Heart, So Is He.” The Parish News: Church of the Holy Trinity, February 1954, Volume LVII, Number 4 edition. Box 27, Folder 3. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

“Lola Graham Du Bois, Aka.” Case Report. New York: 1961. FBI #100-87531. National Records and Archives Administration.

Graham Du Bois, Shirley. 1953. Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable, Founder of Chicago. New York: J. Messner.

———. 1957. “Review of Anna Louise Strong, The Stalin Era (Altadena: Today’s Press, 1956).” New World Review 25 (2): 36–38.

———. 1958. “Letter from Tashkent.” Mainstream 11 (12): 16–21.

———. 1961a. “Negroes in the American Revolution.” Freedomways 1 (2): 125–35.

———. 1961b. “Take Heart, My Brother!” New World Review 29 (4): 24–28.

———. 1962. “Nation Building in Ghana.” Freedomways 2 (4): 371–76.

———. 1963a. “After Addis Ababa.” Freedomways 3 (4): 471–85.

———. 1963b. “5 Days That Made History.” Drum, September.

———. 1966. “What Happened in Ghana? The Inside Story.” Freedomways 6 (2): 201–23.

———. 1967a. “Guinea-Sierra Leone Pact Is a Step to African Unity.” Africa and the World 3 (30).

———. 1967b. “The Little African Summit.” Africa and the World 3 (31).

———. 1968a. “Cairo - Six Months after the Blitzkrieg.” Africa and the World 4 (39): 20–24.

———. 1968b. “Nkrumah’s Record Speaks for Itself.” Africa and the World 4 (42): 18–20.

———. 1968c. “A Ghanaian Questions All-India Radio.” Eastern Horizon 7 (3): 49–52.

Graham, Shirley. 1971. Oral History Interview with Mrs. Shirley Graham Du Bois. Box 1, Folder 1. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

Graham, Shirley. 2001a. “It’s Morning: A One-Act Play.” In Plays by American Women: 1930-1960, edited by Judith E. Barlow, 235–62. New York: Applause Books.

———. 2001b. Track Thirteen. Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street Press.

———. n.d. “Deep Rivers: A Music Fantasy.” Libretto. Subseries G, Plays, Folder 41.17. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

———. n.d. I Got Wings! (unpublished).

———. n.d. Mary (Short Story).

———. n.d. “Oberlin and the Negro.” Crisis 42 (4): 118, 124.

Graham, Shirley, and John Brownwell. 1936. “Mississippi Rainbow (Theme Song Music by Shirley Graham).” Musical Score. Subseries A, Musical Scores, Folders 22.19-22.21, Folder 25.4F. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

Graham, Shirley, and Owen Dodson. 1938. “Garden of Time (Music by Shirley Graham).” Musical Score. Yale School of Drama. Subseries C, Work and Writings, PD.70. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

Graham, Shirley, and Lorenz B. Graham. n.d. Kawo: A Story of Africa (Short Story).

Graham, Shirley. Letter to the editor. 1948. “Letter Sent to the New York Post and New York Star,” June 25, 1948. Box 17, Folder 1. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

Graham, Shirley, and Seldon Rodman. n.d. “The Revolutionists.” Script. Subseries G, Plays, Folder s 42.13-42.17. Shirley Graham Du Bois Papers.

Horne, Gerald. 2002. Race Woman: The Lives of Shirley Graham Du Bois. New York University Press.

“Shirley Graham Writes New Work on Robeson,” July 20, 1946. The Chicago Defender (National Edition).

Van Der Horn-Gibson, Jodi. 2008. “Dismantling Americana: Sambo, Shirley Graham, and African Nationalism.” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture 7 (1): n.p.

Diane Carey, Sarah M. Hutcheon, Lynda Leahy, and Caitlin Stevens helped with research at the Schlesinger Library.

Mary Erickson, Eric Lohman, Sarah Mick, Stephanie Schuessler, Zach Sell, and Janine Zajac provided research support.