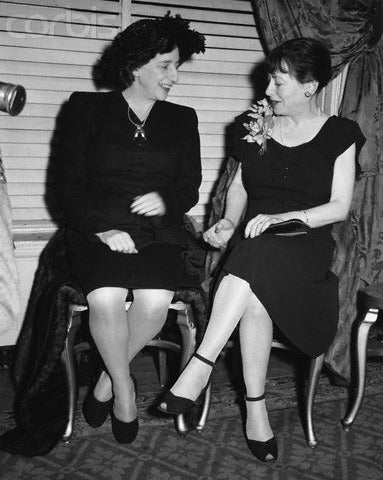

Lena Horne and Hazel Scott

In New York City, then the center of broadcast production, in the years between the two world wars, diverse groups of women had taken advantage of economic and political instabilities to carve out toeholds in media industries. To be a woman who wanted to change the treatment of women on and off-screen in the 1930s and 1940s was to struggle constantly against incredibly rigid and powerful institutions. Along with Dorothy Parker, the Broadcast 41 “dreamed by day of never again putting on tight shoes, of never having to laugh and listen and admire, of never more being a good sport. Never.” They resented having to be good sports when confronted with sexism and racism. They complained that when they lobbied “for an acknowledgment of black humanity,” as did Fredi Washington, they were ostracized and censored. Because of their public criticisms of the entertainment industry, they gained reputations for being intractable, difficult, or vicious. In the words of Lillian Hellman (one of the most famously difficult of the Broadcast 41), “You’re always difficult, I suppose, if you don’t do what other people want.” Where stubbornness and iconoclasm were praised in male colleagues, the personal, professional, and political experiences of the Broadcast 41 reminded them time and again that traits considered virtues in men were fatal character flaws in women.

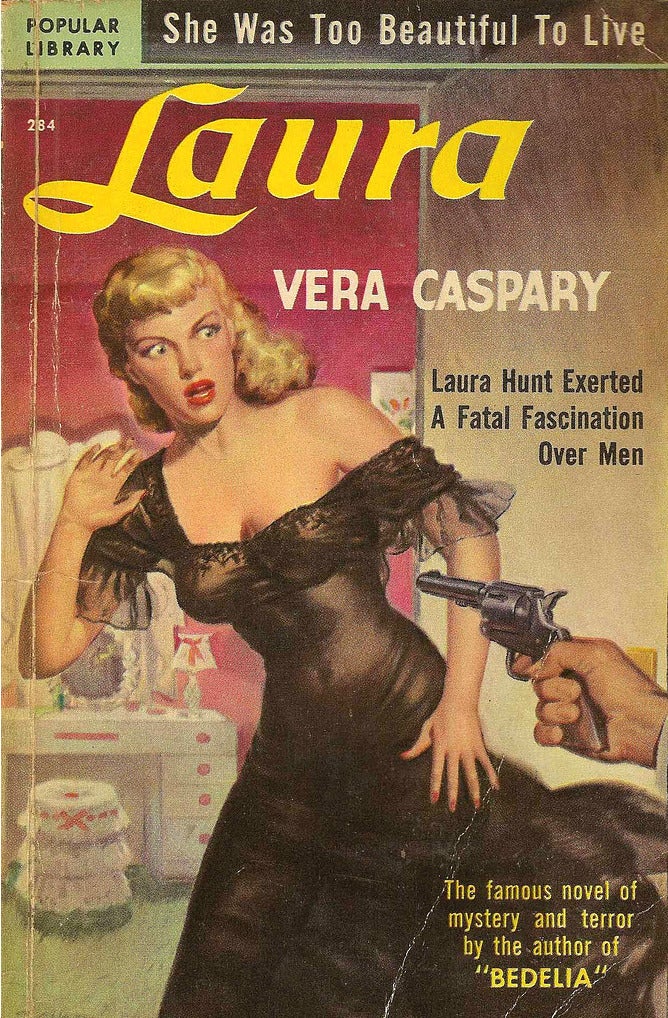

In spite of the hardships they endured, progressive women loved their work. Years later, writer Vera Caspary wrote “work made my life what it has been….everything came through working…independence to live and love and travel; joy in work; heartbreak in work; survival through work.” But they were candid about the challenges. When asked what two characteristics a woman had to have to succeed in show business, Ruth Gordon replied, “imagination and indestructibility.” In order to survive work in media, women needed to be indestructible, in Ruth Gordon’s estimation, or, in the words of one of Gordon’s 21st century descendants, “unbreakable,” like producer, writer, and actress Tina Fey’s sitcom character Kimmy Schmidt. Lena Horne could have been speaking for all of them when, years later, she modestly told the audience for her one-woman show, “I’m just a survivor.”

They were survivors indeed, in an industry that destroyed many talented, independent, creative, and supposedly difficult women. In the years before the blacklist, the progressive women, including the Broadcast 41, not only managed to survive, they developed resources, support networks, and strategies of resistance. At the end of World War II, they looked forward to enjoying some of the fruits of these labors, recognizing that their struggles to be included in media industries—in workplaces and on screens alike—were part of wider efforts to achieve full democracy and social justice. They had no intention of backing down from those fights.

What the Broadcast 41 had made, what they were making when the blacklist occurred, and what they only dreamed of making as reflected in materials like the above add up to a counterfactual history of television, based on a massive alternative archive, a dreamscape of the powerful anti-racist, proto-feminist voices and content that existed before the G-Man’s fantasies became television’s reality.

This history points to the evolution of ideas that might have taken place in television long years ago, if it had continued to respond to the pressure of progressive women and people of color’s work and their powerful criticisms of media industries’ representations of them. This archive of resistance and opposition offers new ways of thinking about audiences as well, minus the power of anti-communists to render women, people of color, and immigrants either unworthy of the industry’s respect or beneath its vision.