Overview

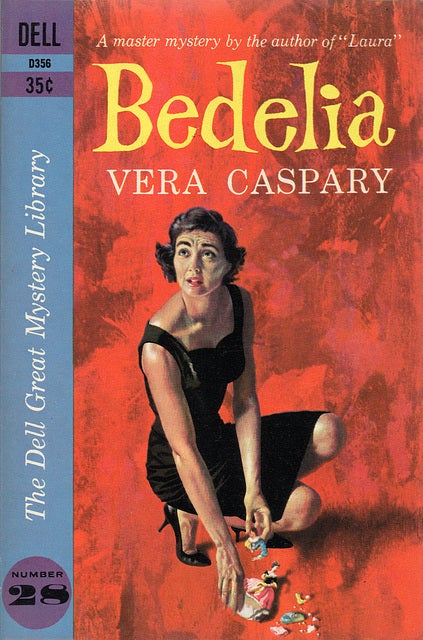

Vera Louise Caspary (November 13, 1899-June 13, 1987) was a novelist, playwright, and screenwriter. Her bestselling novel, Laura, was made into an Academy Award-winning film. Her novels were known for their use of multiple perspectives and her trademark career girls, young women who refused male protection and paternalism in their struggles for independence and autonomy.

Biography

Born in 1899, Caspary was the youngest of Paul and Julia Caspary’s four children. Her mother was in her mid-forties when she became pregnant with Caspary and concealed her “shameful secret” by wearing “tea gowns which concealed her scandalous condition.” Once her mother had recovered from “the horror of having a baby at her age,” the “rest of the family . . . loved, spoiled and bossed me outrageously.”1 However loving, Caspary’s family life--like the lives of many middle class Americans in the early part of the twentieth century--was ideologically and economically turbulent. Both her maternal and paternal grandparents had emigrated to the US in the middle of the nineteenth century and although the family was secular (her paternal grandfather was a self-described socialist and freethinker), they “were contemptuous of Jews who denied being Jewish or changed their names and contradicted ourselves with scorn for those whose names ended in –witz and –ski.”2

Caspary remembered her older sister Irma as the arbiter of these and other class distinctions, a girl who would give “only second-best candy to little girls whose grandparent had Russian or Polish accents” and who preferred that Vera “play with children with the surnames of German-Jewish families who had been in Chicago for at least two generations.” Caspary’s autobiographical novel, Thicker Than Water, a sprawling epic about three generations of the fictional Piera family in Chicago, explored the multifaceted conflicts between Portuguese Jews and the Eastern European Jews they eschewed as “kikes.” The novel was, as Caspary later put it, about “Jewish prejudice toward Jews, the Sephardi to the Ashkenazi, the German Jews to the Russians, Polish, Lithuanian, etc.”3

When her father’s first business venture, establishing a department store in Memphis, Tennessee, ended in bankruptcy, conflicts within the Caspary family intensified. Ashamed of their circumstances, her mother and Irma concealed the frugalities forced upon them by this and subsequent financial disasters, indulging in forms of “self-pity and subterfuge” of which both Vera and her father disapproved. Guilt-ridden, Paul Caspary did not challenge their “constant whine of poverty since he suffered the guilt of a man who believed himself a failure because he could not provide the luxuries to which his women were entitled.”4 Caught between her father’s guilt over his failure to provide and her mother and sister’s consumerist desires, these formative experiences engendered in Caspary a critical perspective on the gendered expectations of normative families. For the remainder of her life, Caspary would understand the spitefulness of class envy as a distinctly feminized practice and she remained acutely aware of the powerful role that women played in enforcing norms of gender, at the expense of both women and men.

The Casparys were progressives to their core. Paul Caspary had grown up in an abolitionist family in Milwaukee and Vera grew up on a street that was in the midst of integrating: Rhodes Avenue in Chicago, which later became the center of Chicago’s Black Belt. The first blacks to move into their neighborhood—in fact, into the second unit of their double house—were groundbreaking journalist were anti-lynching activist Ida Wells Barnett and her husband, Judge Ferdinand Barnett. According to Caspary, Paul was among a group of white residents who resisted the racist backlash directed at the Barnetts, although as she later observed, they seldom socialized with their black neighbors.5

Alienated from her mother and sister’s consumerism and economic disappointment, which encouraged her to view women who worked for a living with “pity and contempt,” Caspary understood financial independence to be the key to success and happiness. Years later, she told a reporter “When I was just a little girl, I knew that I wanted to be a writer, and I took the necessary steps, through study and through making myself financially independent, to make my dream come true.”6 After graduating from high school in 1917, Caspary enrolled in a six-month course at a business college. She completed the course in January 1918, “put on a new hat, buckled my galoshes, rode downtown on the El and became a liberated woman.”7

Like other aspiring writers of her era, Caspary hoped “to find a job as a girl reporter.”8 Instead, she found a series of low-paying secretarial jobs, quitting before her boldness cost her the jobs. She landed a job with a wholesale grocer--“a Socialist who enjoyed exploiting capitalists”--handling his correspondence and managing his office while he travelled, eventually preparing all the promotional materials for the grocer’s “questionable merchandise.”9 In what was becoming a pattern, she moved up the ranks quickly, graduating from stenographer to writing marketing copy and promotional materials. Nevertheless, “an assiduous student of want-ads,” Caspary had set her goals higher than the secretarial pool. She continued to send out letters describing her work experience and skills and--cagily--signing the letters “V.L. Caspary.”10 She received many interviews this way, only to find that “’when a ninety-five pound, five-foot-one girl turned up, the advertisers were angry or amused. None gave me a job.”11

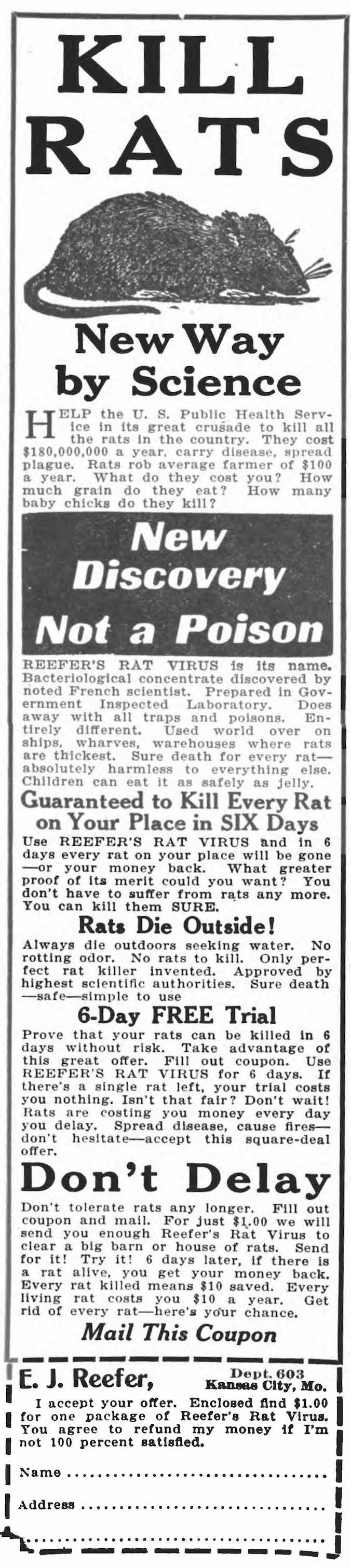

In 1920, Caspary was hired by a large Chicago advertising agency, where she eventually “got her boss’s job, and was paid $35 a week. (He had been paid $125 a week, but she was too proud and happy to care.)”12 Here, she wrote her first headline, “Rat Bites Sleeping Child!,” for an ad selling E.J. Reefer’s Rat Virus, a product endorsed by an organization Caspary had created for this purpose, called The Rodent Extermination League of America.

The product didn’t sell very well because the virus didn’t work, but the agency took note of Caspary’s writing skills and gave her additional accounts.

Over the course of these jobs, Caspary learned a great deal about how the industry understood and addressed female audiences. During her three years in advertising, this devotee of Anatole France, H.L. Mencken, and irony learned to write copy “so simple any semiliterate housewife would understand on sight that she would get her dollar back if Mrs. Reefer’s Washing Tablets did not get her wash whiter than any soap on the market.” 13 In order to succeed, she mastered a style of writing for a female audience considered frivolous and unintelligent, proving successful at creating mail order campaigns in the process.

- 1Vera Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979, 1-3.

- 2Ibid, 8.

- 3Ibid, 7.

- 4Ibid, 17.

- 5Ibid, 17.

- 6Carol Soucek, “Are Today’s Women Really Liberated?” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, 7 April 1975, B-1.

- 7Vera Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 37.

- 8Ibid, 44.

- 9Ibid, 48.

- 10Ibid, 41.

- 11Ibid, 44.

- 12Ann L. Warren, Word Play: The Lives and Work of Four Women Writers in Hollywood’s Golden Age, Unpublished dissertation, University of Southern California, May 1988, 41.

- 13Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 53.

Above: Caspary's bestselling novel, Laura, was made into an Academy Award-winning film.

One of these ads, for Sempray Jovenay pink cake soap, featuring testimonials from one of the two fictitious female founders of the company, shows Caspary’s emerging style:

Nora and I, being women, think we know more about the BIG THING all women want than all the male psychologists you could pack in the Mormon Temple. What do women want? No mere man can answer that. But Nora and I know that the pink cake of sem-pray jo-ve-nay is going to give them a big part of IT.14

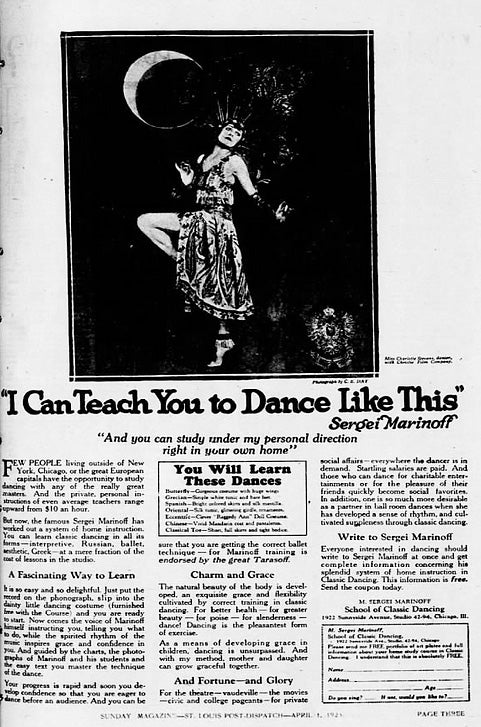

Around the same time, Caspary also created two successful mail order campaigns. One offered dancing lessons with a fictitious authoritarian dance master--a Russian refugee from the Communist Revolution, no less--named Sergei Marinoff, proprietor of the equally fictitious Sergei Marinoff School of Classic Dancing. Marinoff’s letters to his students--typed on gold embossed letterhead Caspary had found in the company’s basement--began with an admonishment to recalcitrant students: “Why have you not sent me your examination on lesson one? What is the matter?” Sergei Marinoff proved so popular that “Pupils fell in love with Marinoff, baked cakes, knitted mufflers, autographed photographs and wrote love letters to a man who did not exist,” even going so far as to brag in later years that they had studied directly with the Master.15

The second correspondence course would have more direct relevance for Caspary’s future career: the Van Vliet Course in Photoplay writing. For this campaign, Caspary learned about writing for movies on the fly, using William Archer’s Playmaking and George Pierce Baker’s Dramatic Technique in order to assemble an introductory course for “students of uncertain intelligence.” “It was very educational. For me,” Caspary wrote.16 She later applied her own lessons to the plays and scripts she wrote in the 1930s and 1940s.

Caspary’s work in advertising and magazine writing introduced her to skills she would later use in writing novels and screenplays for musicals as well as a social world that formed the backdrop for settings in novels like Evvie, Thelma, and Laura. But the repetition and absence of creative possibilities had begun to bore her--the sense that she was nothing more than “a computer that produces variations when different buttons are pressed.”17

Caspary gave advertising “up when I realized that one wrote the same thing over and over again, whether it was for cold cream or plumbing fixtures.”18

In 1922, despite the promise of a raise and bigger accounts, Caspary quit her job, picking up freelance work instead, and settling down to finish her first novel. Caspary had been supporting her elderly parents with her wages. Two events in 1924 effected “an overnight transformation,” turning her into “the man of the family”: the death of her father and the murder of young Bobby Frank, a crime that rocked the Jewish community of Chicago to its foundations and made Caspary for the first time interested in violence.19 When MacFadden Publications offered Caspary a job as assistant editor of Dance Lovers Magazine, she packed up her belongings and her mother and promptly moved to New York City.

Caspary continued to freelance for Dance Lovers, True Story, Trianon Topics, and Finger Print and Identification Magazine. For Finger Print and Identification Magazine, Caspary wrote an article touting the benefits of fingerprinting from a woman’s perspective, as well as the virtues of female police officers. But Caspary was characteristically restless, unhappy with her editor, and disabused of the “heavy luggage of illusion” that had led her to believe that “sincerity and good grammar could improve a McFadden magazine. “I should have known better,” she chided herself.20 She also detested her patriarchal boss Bernarr McFadden, his crusade against doctors, and his weird and obsessive health regimen that, according to her, resulted in the deaths of two of his children.

In her own way, Caspary too dreamed of a class mobility that would allow her to write the novels she wanted to write rather than continue to produce repetitive, alienated copy for an industry she had grown to dislike. Unlike other writers affected by the blacklist--Jean Muir, Gertrude Berg, Anita Loos, and Lillian Hellman--Caspary had come close enough to poverty to spend the remainder of her life seeking to avoid it. Her comparative lack of class privilege meant that she knew that in order to “be truly liberated, a woman should be financially independent” and that in order to be financially independent, she would haveto work at jobs that were distasteful and often unfulfilling.21 Of her experiences as a screenwriter, years later she observed, “I loathed writing screen plays and only in the beginning when I needed jobs accepted such assignments. Later, when I could make my own terms, I worked only on original stories constructing them as screenplays and letting some poor sucker do the dirty work.”22 Writing for advertising, film, and commercial venues paid the bills and provided Caspary with security.

In her autobiography, Caspary wrote about the contradictory predicament of working-class writers like herself,

If I talk too much about earning and spending, it is because money was the basis of all decisions. I was never greedy, never wanted money for show, could quit or turn down a job if it did not please me. Relations and family friends called me Bohemian; Bohemians said I was bourgeois. The bourgeois side demanded comfort, cleanliness, pleasant surroundings, a small degree of security. In an emergency I had no one to turn to.23

In a more self-reflexive language than that of subsequent generations of white, middle-class feminists, Caspary notes the class and gender dimensions of this contradiction: she desired the very consumerist life style she criticized, “the dependence and luxury they had told me was my woman’s due,” but she did not desire a husband or children.24

- 14Vera Caspary, “Vera Caspary Scrapbook,” Vera Caspary Papers.

- 15Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 57.

- 16Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 64.

- 17Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 69.

- 18Albert J. Elias, “Forward Women, Says Vera Caspary,” New York City Compass, 26 July 1950.

- 19Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 87.

- 20Warren, 66.

- 21Soucek, B-1

- 22Vera Caspary, Vera Caspary Papers, Box 28, Folder 5, “Correspondence from Readers."

- 23Warren, 67-8.

- 24Vera Caspary, Thelma, Boston: Little Brown, 1952.

In luxurious houses, around pools, in rumpus rooms and bars, people whose talk had once centered around the frustrations of the movie writer, now argued about Fascism, social security, FDR, and the tactics of labor leaders. The time was ripe for it with the rise of Hitler in Germany, the stories of concentration camps, persecution of Jews, the aggressions of Mussolini, starvation persisting in the United States, union organizers thrown into prison, radicals manhandled by sheriffs’ deputies, poor people and Negroes deprived of justice.1

With the benefit of hindsight, Caspary recalled her experiences with the CPUSA with cynicism and some bitterness, painting a picture of a generation of hypocrites who sought to assuage guilty consciences by playing at revolution. But when Caspary joined in the 1930s, she was younger, more idealistic, and confident that the CPUSA, unlike either the Democratic or Republican Parties, was committed to fighting against racial and economic injustice. Along with writers and intellectuals such as Adrian Scott and her good friend Sam Ornitz, Caspary began gravitating toward the Communist Party some time in the 1920s, finally joining some time during the Spanish Civil War.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Jewish-Americans like Caspary shared African Americans’ broadly anti-anti-communist sentiments. Having inherited her father’s anti-racist convictions and growing up within a largely progressive Jewish community in Chicago during the Depression, socialism seemed a perfectly reasonable alternative to the capitalist system that was failing so many people throughout the world. And the atmosphere in Hollywood in the 1930s was politically and intellectually heady. Hollywood “was aflame with argument. It was alive and at its best, particularly among picture people,” Caspary later remembered, “There were lectures, seminars, parties of all kinds, raising money for Britain, for Russia, for refugees, etc. There was dancing, there was mingling ($5000 a week people talked to $500 a week bums), the left wing solicited the right, social lines were forgotten, and we stayed up later than in peace time.”2

According to her own account, Caspary did not join the CPUSA until some time in the winter of 1937, but her sympathies were already clear in an article she wrote for the Chicago Defender in 1932 about the nine young men accused of raping two white women in Scottsboro, Alabama. Urging solidarity between the NAACP and the CPUSA’s International Labor Defense in the case, Caspary supported the CPUSA’s position, writing that the imprisonment of the Scottsboro youths was “not only a crime against black people, but a crime against all those poor ignorant working people, the mill hands and the tenant farmers, the poor Colored and the poor white in the South.”3

By the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Caspary actively participated in party work, “petitioning for blockades, for collective security, for aid to the victims of aggression. She attended meetings with cells in New York and Connecticut. “In Connecticut gardens and New York living rooms,” she recalled, “we gathered to pledge our faith in a way of life that would give men and women the strength, the dignity, the equality of opportunity that we believed was the human lot in the Soviet Union.” Working for the Republican cause in Spain, Caspary recalled, “we grew sturdy and proud of membership in the only movement in the world (we were told) that would abolish poverty and raise to prosperity and equality the wretched of the earth.”4

In Norwalk, Connecticut, Caspary had been introduced to a group of factory girls by an undercover agent for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers. There being “no other place in town where girls of Italian, Polish and Hungarian descent could engage in organized recreation,” Caspary began holding weekly meetings of a group that called itself the Confidences Club. Although the CPUSA considered these meetings to be party activities, Caspary said that the group’s purpose was education and socialization of a sort that most working-class girls didn’t get to experience. But the group likely had been infiltrated and when Caspary told one of the girls who was seeking advice about birth control to visit the Birth Control Association in New York, the Confidences Club made the local headlines, with a story that said that its leader advocated free love and was bringing communism to Connecticut.5 Although Caspary wasn’t identified by name, that was the end of the Confidences Club.

From the beginning, Caspary loathed the secrecy that caused her to be instructed “to join the Party under an alias,” the logic being that her “name as a writer would be of greater value . . . if I were not known as a Communist.”6 She would “serve better in secrecy,” she was told, since an “uncommitted writer would have greater influence on the prejudiced bourgeois reader than an acknowledged Communist.”7 “The discipline of silence,” she recalled, made her question her reasons “for joining the Party,” namely the “search for honesty, the questioning of values,” and created in her eyes a culture in which “any questioning is called treason.”8 The discipline of silence made doubly suspicious the excuses CPUSA leaders offered about “the Soviet purges, the trials of old Bolsheviks, executions, labor camps in Siberia,” which they predictably enough attributed to the machinations of “the lackey capitalist press and wicked Trotskyites.”9

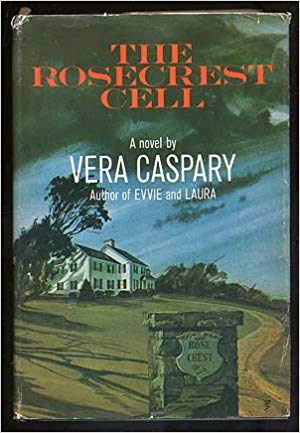

As a feminist, Caspary was also dismayed by the Communist Party’s gender politics. In The Rosecrest Cell, a novel she later describe as “a confession disguised as a novel about my two and a half years in the Party,” one of the party faithful – who symbolizes all the contradictions and shortsightedness of the party itself — confides in his comrades, “I’ve always supported the woman question, but hell, boy, I was on the [Federal Theatre] Project. Writers. Try running an office with a bunch of females who are off half the time with cramps. I could provide a biologist with some very valuable statistics. Stenographers menstruate twice a month.”10

These frustrations were amplified by Caspary’s growing resentment about the CPUSA’s attempts to dictate the content of her novels. She blamed her inability to complete a novel during the time she was a member on the party’s insistence that she write a proletarian novel. Although she claimed that she agreed with the mandate that she must use her writing “To improve the conditions of living for all men,” she fiercely disagreed with the Party’s prescriptions about what constituted a “solid piece of proletarian literature.”11 One example of this conflict was Caspary’s run-in with Frontier Films, a Popular Front film collective with ties to the CPUSA.12 Asked about her experience with Frontier Films in the 1970s, Caspary told scholar William Alexander that she and her collaborator George Sklar “had a terrific argument” over their screen play for Pay Day, a play about child labor. “We had submitted a screen play,” she wrote Alexander, “which they changed sadly; they called it a shooting script but it was like no shooting script I’ve ever seen in Hollywood. Completely amateurish. And, as I remember, lifeless. So we were very angry and quit.”13 “They treated us worse than a Hollywood producer would have,” Caspary added in a conversation with scholar Ann L. Warren, “A Hollywood producer would at least have employed a professional to do the rewrite.”14 Frontier Films had also, erroneously according to Caspary, used her name on their letterhead without her authorization, a use that would come back to haunt her when this erroneous formal association with Frontier Films would be cited by anti-communists.

Her work in advertising and film had given Caspary far too much experience in what it was like to produce writing within the unyielding constraints of an industrial system. Caspary, moreover, did not like to collaborate. She was, as one colleague put it, “well-known as a wit, a bright woman, a good popular writer,” but it was equally well-known that “She never cooperated with anyone on a screenplay.”15 For her to experience similar forms of control on the part of a political party she believed to be in the business of liberation was, to her thinking, the final straw.

In April 1939, Caspary decided she would visit “Russia to see how people lived in a world that to the Daily Worker was a paradise, to the Daily News hell.”16 Although Caspary spoke glowingly of her visit in public, she found Moscow to be strewn with images of Stalin and tense “from the sense of constant surveillance.”17 When Stalin signed the non-aggression pact with Hitler in 1939, Caspary notified the CPUSA secretary of Connecticut that she was quitting. She also gave her “word that I would never betray the Party or reveal its secrets, although what there was to conceal I could not imagine since everything we had ever discussed was shouted at public meetings and openly declared” in party publications. The only real secrets she knew “were the names of members who could become victims of professional Red-baiters.”18

On the eve of the United States’ entry into World War II, Caspary fell in love with British film producer Isadore “Igee” Goldsmith. Separated for much of the war, the couple began living together in 1945. In 1950, finally married to Goldsmith, Caspary was at the top of her game. Her stories were selling well in Hollywood and, accepting work only on adaptations rather than original stories, Caspary contracted for five-week stints, which left her plenty of time to work on the novels that were “the purpose of all my screen jobs.” In the lulls between her lucrative contract gigs, Caspary “wrote as I liked, telling stories for the story’s sake, pleasing myself in the creation of incident, the development of character, the weaving of a theme.”19

Fresh from working on the film Three Husbands, a comedy starring Eve Arden and Ruth Warrick, Caspary had just sold a treatment to MGM for $50,000 –- over $400,000 in today’s dollars. In 1951, Caspary would earn $55,000 from MGM alone. But then the sky came crashing down. Listed in Red Channels in 1950, Caspary’s career in the film industry began to take a slow nosedive, cushioned somewhat by screenwriting projects that were already under contract. By 1960, Caspary was earning a meager $2,500 a year.“20 She enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle that supported frequent travel to Europe, she had houses in Hollywood and Connecticut, and she and Goldsmith had no expenses associated with children or elderly parents. Moreover, aside from the script for Pay Day that was never made, Caspary’s commercial work had never been reflective of her political views and she understood her screen jobs as little more than a means to the end of her fiction writing.

But anti-communists made no distinction between past and present political sympathies. For them, once infected with the communist bug, the only cure was public renunciation. As Caspary put it, “The skeleton in my closet carries a hammer and a sickle” and that closet contained examples of what anti-communists considered subversive activities.22 Her support for numerous anti-Fascist events in the 1930s provided anti-communists with a trail of public documents to follow. In 1943, Caspary had been described as a fellow traveller in an FBI Special Agent’s report on communist infiltration of the motion picture industry. The report noted that she taught screen writing for the Hollywood School for Writers, an organization founded by the communist-sponsored League of American Writers (both groups ceased to function in January 1943, which demonstrates the unreliability of much of the information in the report, which assumed that these organizations were still functioning in 1950).23 Despite the largely apolitical content of her commercial work, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI were suspicious of film noir and jealous of its successes, believing noir’s renderings of crime, criminals, and detectives to be too ambivalent (particularly when it came to masculinity) and not hard enough on crime and criminals. The trip to Russia in 1939 seemed the icing on the anti-communist cake.

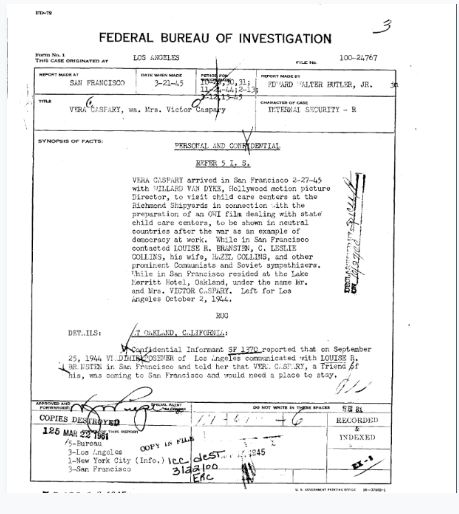

Still, it’s likely that Caspary’s history would not have come back to haunt her if it hadn’t been for a request she made in 1944: to visit childcare centers at the Richmond Shipyards in San Francisco. The purpose of her visit to the childcare centers was to produce an Office of War Information (OWI) film “dealing with state child care centers, to be shown in neutral countries after the war as an example of democracy at work.”24 For an FBI already concerned Hollywood pictures “will have an effect on some classes of the American people, which will not be in the interest of the American form of Democracy,” Caspary’s request raised flashing red flags.25

In the first place, as the FBI put it in their October 1943 report on Hollywood--one of two major reports conducted in that year--Hollywood’s un-Americanism was being promoted not just by communists, but by immigrants and the children of immigrants who “harbored ‘ideas and culture’ alien to ‘the ideals and traditions of America’ . . . . and [who] naturally carried with them an ‘instinctive racial affinity inherited from European social life’ which, revolutionary or not, was deemed un-American.”26 A Jew, a Communist, and the daughter of immigrants, Caspary’s motives were inherently suspect. Hoover had additionally conceived an antipathy toward the Office of War Information that made him distrustful of all their requests. Perhaps most importantly, Caspary’s interest in childcare and the link she made between childcare and democracy was fully subversive in the context of an emerging Cold War culture that understood women’s work in the waged economy and childcare as communist conspiracies to undermine family values and patriarchal control.

- 1Vera Caspary, The Rosecrest Cell, New York: W.H. Allen, 1968, 39-40.

- 2“Letter to Faith Logotleth,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 5, “Correspondence from Readers,” n.d. probably 1981).

- 3“Vera Caspary, “What Price Martyrdom?” Chicago Defender (9 January 1932), 14.

- 4Vera Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 177.

- 5Ibid, 177.

- 6Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 178.

- 7Caspary, The Rosecrest Cell, 54.

- 8Ibid, 363.

- 9Caspary, Thicker Than Water, 178.

- 10Ibid, 179.

- 11Caspary, The Rosecrest Cell, 58.

- 12See William Alexander, “Frontier Films, 1936-1941: The Aesthetics of Impact,” Cinema Journal (Volume 15, Number 1, 1 October 1974), 16-28, for more on Frontier Films and the popular front.

- 13“Letter to William Alexander,” Vera Caspary Papers, Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence, 22 June 1975.

- 14Ann L. Warren, Word Play: The Lives and Work of Four Women Writers in Hollywood’s Golden Age, Unpublished dissertation, University of Southern California, May 1988, 75-6.

- 15Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle, Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist (New York: St. Martin’s, 1999, 244.

- 16Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 182.

- 17Ibid, 187.

- 18Ibid, 119.

- 19Ibid, 230-231.

- 20Memo from Bernard Skadron, Public Accountant,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence).[/fn]

Like many of those listed in the pages of Red Channels, by 1950, Caspary’s political perspectives had drifted from the radical left more toward the center. According to Norma Barzman, Caspary and Goldsmith continued to travel in leftwing circles – it would have been impossible to avoid those in the Hollywood of the early 1940s, but whatever communist sympathies she might have harbored were safely in the past.McGilligan and Buhle, 3.

- 22Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 169.

- 23“Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry,” Special Agent Report, Los Angeles, FBI (18 February 1943 (Leab 1991), Reel 1, 162-3.

- 24FBI Memorandum, 21 March 1945.

- 25Quoted in John Sbardellati, “Brassbound G-Men and Celluloid Reds: The FBI’s Search for Communist Propaganda in Wartime Hollywood,” Film History (20, 2008), 419.

- 26Ibid, 415.

A memorandum J. Edgar Hoover wrote to the Special Agent in Charge of the Los Angeles Bureau subsequently transformed Caspary’s request into something sinister. Entry to the Richmond Shipyards child care center, Hoover, wrote, would put Caspary in “a position to obtain vital information concerning this nation’s war effort which might be detrimental to the best interests of the United States should it be passed on to a foreign power with which Vera Caspary was sympathetic.” “You will recall,” Hoover continued, “that Vera Caspary has been mentioned on numerous occasions in the various reports submitted in connection with the Comintern Apparatus.” The Caspary woman’s activities,” Hoover concluded, “should be given immediate, thorough, and discreet investigative attention.”27

Caspary’s request started a chain reaction within the FBI. Before this request, Caspary had not been a target of FBI investigation, although her name had appeared in reports about the subjects of other investigations. Her request caused the FBI to search their files for these references and begin an immediate investigation into her current activities. The dossier they compiled on her revealed that her name had appeared as early as 1938 in reports on other individuals that had been submitted to the FBI by special agents and “unknown outside” sources.28

The Bureau correctly noted that Caspary had been active in communist organizations in Connecticut, New York, and Los Angeles. She had written what the FBI considered an inflammatory statement for a pamphlet entitled “Writers Take Sides,” that included the assertion, “if I can use my training and experience as a writer to fight against fascism, I want to do as much as I can.” Caspary’s name had also appeared in the Daily Worker, on one occasion as a signatory to a manifesto denying the Moscow purge trials. According to an article received by an “unknown outside source,” Caspary had attended a state conference on civil rights held in San Francisco in 1941. In addition, Caspary’s name had appeared in lists of Screen Writers Guild members considered to be leftists and that films that she had worked on like Danger Signal (1945) were said to “perhaps . . . contain information of a propaganda nature.”29

The FBI initially turned its attention to prosecution, in Caspary’s case determining whether there had been a violation of the Hatch Act, which prohibited federal employees from membership in organizations advocating the overthrow of the US government. Meanwhile, the FBI also began to monitor Caspary’s daily activities, authorizing surveillance of her mail and telephone records for a period of 30 days, although according to their records, the FBI continued this surveillance for several months beyond the original one-month period. Her bank and credit information were accessed and recorded and her voter registration was pulled (“her Party affiliation is Democratic,” according to the report).30 The FBI also noted that the unmarried Goldsmith and Caspary had stayed in hotels under the aliases “Mr. and Mrs. Caspary.” The FBI additionally interviewed former acquaintances of Caspary’s, like filmmaker Nanette Kutner who had lived with Caspary in New York City in the 1930s. The report on Caspary listed six separate confidential informants, along with the testimony of hotel clerks.

Although the FBI cited sources claiming that Caspary had twice tried to get passes to enter war plants, but had been turned down both times, it seems highly unlikely that Caspary was engaged in espionage during World War II.31 Her friendship with Vladimir Pozner, who headed the US War Department’s Russian film section during World War II and was later identified by the Venona Project as having been in contact with Soviet intelligence during that time, may have increased the FBI’s attention to her.32

After this spate of activity, the FBI file on Caspary remained inactive from June 1945 until August 1950, until June 30, 1950, after the publication of Red Channels, when anti-communist convert and professional informer Louis Budenz identified Caspary as one of 400 “concealed communists.” “During the 1940’s,” Budenz wrote, “I was advised that Miss Caspary was a Communist._3 FBI memoranda also reproduced the affiliations cited in both Red Channels and Vincent J. Hartnett’s File 13, again demonstrating anti-communists’ networks of shared information.

In 1951, Caspary was summoned to appear before executives at MGM. She was informed that she was on a gray list and confronted with a list of 24 political transgressions. According to the notes she typed up after this meeting,

The twenty-four items were read aloud by Mr. Franklin [one of M.G.M.’s “clearance men”] in a sepulchral voice after he had made a solemn speech about the embarrassment I had caused M.G.M. It seemed that the two stories I had sold the studio (at extremely generous figures, Mr. Franklin reminded me) could not be produced unless I denied these charges and answered another and more pointed question.34

Mr. Franklin cited her inclusion in Red Channels, which Caspary referred to as “that noxious compendium,” as further evidence of her subversive activities.

Studio executives advised Caspary that unless she “wrote a letter to Mr. Nicholas Schenck, then head of the company, humbly asking forgiveness and confessing that I was not and never had been a Communist,” they would be unable to hire her again.35 “I wrote a letter,” Caspary acerbically added, “minus the confession.” Desperate, having seen what had happened to other writers, Caspary flatly denied that she had ever been a member of the Communist Party. Like Jean Muir and Hazel Scott, Caspary also refused to name names.

In her autobiography, Caspary claimed that the lie haunted her for years, but that writing the letter was the only way for her to continue work on the musical Les Girls, a commercially perfect “Caspary stew--dancers, European travel, comedy, romance.”36 But her refusal to name names, which according to the logic of The Road Back was the only true way to rehabilitate a career tainted by the blacklist, meant that she would never be fully above suspicion. Unlike friendly witnesses like Gary Cooper, Ronald Reagan, and Louis B. Mayer or converts to anti-communism who renounced their previous political affiliations and named names in order to “rehabilitate” their careers like Edward Dymtryk and Elia Kazan, Caspary’s refusal to name names meant that the specter of the blacklist would continue to haunt her future work in film and broadcasting.

Despite her denial of party membership, the blacklist continued to dog Caspary. Twentieth Century Fox fired her from work on a musical adaptation of Daddy Long Legs while she was on location in Austria, refusing “to have me adapt a silly comedy because of my Red reputation.”37 Her antipathy toward Hollywood intensified, as conflicts between those who had been blacklisted and those who named names made it difficult to socialize. “You couldn’t go to a restaurant and talk to one group of people without another group looking down on you,” she recalled. Hollywood had become a “most ghastly town. It was as if a gray cloud had descended over it.”38

After the blacklist, dissatisfied with the climate in Hollywood, Caspary began to shop television screenplays to networks.39 She had little success. She wrote some uncredited episodes of the Twentieth-Century Fox Hour in the mid-1950s; in 1956, she wrote the play Wedding in Paris with Sonny Miller; and in the early 1960s, Laura was adapted for television.

But her trademark career girls and independent women no longer appealed to networks, advertisers, and sponsors selling postwar domesticity. Her pilot for Apartment 3-G (which, like the comic strip it was based on, revolved around the lives of three single girls)40 and "The Private World of the Morleys" 41 (whose central conflict involved the decision of the patriarch’s granddaughter to follow in his footsteps and become a surgeon) were never made.

The blacklist conspired with age against her as well. Monica McCall, her agent, said as much concerning one such rejection, for a police procedural featuring two investigative reporters committed to both the scoop and social justice. “So sorry,” McCall wrote to Caspary, “but the television people feel that The Reporters idea really isn’t fresh enough for them to get any sort of step deal.” McCall added, “Heaven knows, one never sees anything particularly fresh on television, and I have often been told that such-and-such an idea was ‘way out’ and not likely to appeal to middle America!”42

In many ways, Caspary’s story was exemplary of her generation. Like thousands of other writers and artists, Caspary was swept up by political currents and events in the 1920s and 1930s. The CPUSA appealed to liberals like Caspary on the basis of their anti-Fascist and anti-racist beliefs at a moment in time when the two-party system was failing to provide alternatives. As Philip Dunne said of the Popular Front era “It was not a question of liberals ‘fellow-traveling’ with Communists, but Communists ‘fellow-traveling’ with liberals.”_3 When this rapprochement no longer held -- for many liberals, it broke down in 1939--they left the party, although remaining true to what had always been their core liberal beliefs.

But their core liberal beliefs had been transformed by anti-communists into something subversive and un-American in the context of Cold War America, even for white middle-class women like Caspary who believed in the value of hard work and free enterprise. Like the middle-class women who would re-enter the work force in record numbers in the 1960s, Caspary believed in the value and potential uplift of work. For Caspary, “Everything good in my adult life has come through work: variety and fun, beautiful homes, travel, good friends, interesting acquaintances, the fun of flirtation and affairs, and best of all, the profound love that made me a full woman.”44 As she once wrote in Evvie, “Evvie and I lived our own lives because we paid our own way.”45 Yet having once belonged to the party, in the eyes of anti-communists, she would always belong to it.

After her beloved Goldsmith died in 1964, Caspary moved back to New York City, where she lived “in Greenwich Village, on the very edge of the swinging Eastern section.” What she saw on the streets around her, she told an old friend in a letter, “is unbelievable. Old Army coats and tophats, a beautiful Negro in blue jeans and a derby, boys with long hair tied back with ribbons, boys with a single earring, painted faces, beads; girls in ball dresses of 1920 or 1930 worn over boots.” Caspary relished the decade’s “open criticism and vehement opposition to power” and forms of commentary that were “more open, rancorous and (even) slanderous than I have ever seen it.”46

But her assessment of progress on women’s liberation was less upbeat. In a 1975 newspaper interview, Caspary observed that her novel The Dreamers set out “to show today’s woman that she is not more liberated than her 1920s counterpart,” adding that women of yesteryear were “not too different from today. Those women, torn between their need for a sense of accomplishment, love, marriage, society’s approval and money, had the same motivations as the ‘70s libber.”_7 When asked at the end of her life whether she had experienced conflict between her own identity as a woman and her identity as a novelist, Caspary sharply replied, “And why should there be conflicts about being a woman and a creative artist (your phrase)? Women were among the earliest novelists and were important in the development of the form. If by conflict you mean the diversion caused by domestic duties, I can happily report that there were none in my life.”48 For Caspary, liberation did not lie in the sexual revolution: “being free has nothing to do with how many affairs you allow yourself. After all, we don’t all need the same number, do we?” Instead, being free meant liberating one’s self from “worrying about what your mother and family and friends are going to think every time you feel that you need to do something.” Caspary understood liberation to result from two things: financial independence and living one’s life with what she referred to as “conviction,” or the independence of thought that allowed women to avoid the desire to “have someone tell them what to do,” or having someone tell them what they wanted.49

Caspary’s convictions about women’s independence were un-American in the eyes of anti-communists. It would take the television industry another two decades to begin addressing many of the issues the blacklist had made impermissible, like women in the workplace, women in higher education, or women aspiring to more than marriage and children. In the cases of writers like Shirley Graham and Vera Caspary, their ideas about heroic people of color and independent-minded women would be prevented from appearing on television screens until at least a decade after the civil rights and feminist movements burst onto the scene.

Google Drive: See Vera Caspary's FBI File.

- 27FBI Memorandum, 18 January 1945.

- 28FBI Memorandum, 11 November 1944), 2.

- 29FBI Memorandum, Los Angeles Field Office,10 July 1943, 1-2.

- 30FBI Report (31 March 1945), 3.

- 31FBI Memorandum from Special Agent in Charge, LA to FBI Director (2 December 1944), 1.

- 32Vera Caspary, “Letter to Valodia Pozner,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence, 10 January 1968).

- _3FBI Memorandum, from Special Agent in Charge, New York to FBI Director (8 August 1950), 4.

- 34Vera Caspary, Undated Memorandum, Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 4).

- 35Vera Caspary, “Letter to Allan A. Mussehl,” Vera Caspary Papers (General Correspondence, Box 28, Folder, 17 July 1979).

- 36Caspary, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, 261.

- 37Caspary, “Letter to Allan Mussehl,” 2.

- 38Quoted in Victor S. Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003).

- 39Caspary, “Letter to Allan A. Mussehl (17 July 1979).

- 40Vera Caspary, “Apartment 3-G: Lonely Saturday,” Vera Caspary Papers.

- 41Vera Caspary, “The Private Life of the Morleys,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 30, Folder 7, General Correspondence).

- 42“Letter from Monica McCall,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence, 25 September 1974).

- _3Sbardellati, 416.

- 44Warren, 91.

- 45Vera Caspary, Evvie, New York: Harper, 64.

- 46Vera Caspary, “Letter to Valodia Pozner,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence, 10 January 1968).

- _7Soucek, B-1.

- 48Vera Caspary, “Letter to Miss Schwartz,” Vera Caspary Papers (Box 28, Folder 1, General Correspondence, 16 October 1977).

- 49Soucek, B-1.

Bibliography

A Manual of Classic Dancing. (as Sergei Marinoff) Chicago: Sergei Marinoff School, 1922 (Non-fiction)

Ladies and Gents. NY: The Century Company, 1929

The White Girl. NY: J.H. Sears & Company, 1929

Music in the street. NY: Sears Publishing Co., 1930

Thicker than Water. NY: Liveright, 1932

Laura. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943

Bedelia. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1945

Stranger Than Truth. NY: Random House, 1946

The Murder in the Stork Club. NY: AC. Black, 1946

The Weeping And The Laughter. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1950

Thelma. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1952

False Face. London: W.H Allen, 1954

The Husband. NY: Harpers, 1957; London: W.H. Allen, 1957 (with dust-wrapper by George Adamson)

Evvie. NY: Harper, 1960

Bachelor in Paradise. NY: Dell, 1961

A Chosen Sparrow. NY: Putnam, 1964

The Man Who Loved His Wife. NY: Putnam, 1966

The Rosecrest Cell. NY: Putnam, 1967

Final Portrait. London: W.H. Allen, 1971

Ruth. NY: Pocket, 1972

Dreamers. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1975

Elizabeth X. London: W.H. Allen, 1978

The Secrets of Grown-Ups. NY: McGraw Hill, 1979

The Murder in the Stork Club and Other Mysteries. Norfolk, VA: Crippen & Landru, 2009. Collection of novelettes.

Short Stories

"In Conference"

"Marriage '48", Colliers, Sept–Oct 1948

"Odd Thursday"

"Out of the Blue", Today's Woman, Sept 1947

"Stranger in The House", 1943

"Stranger Than Truth", Colliers, Sept–Oct 1946

"Suburbs"

Plays

Blind Mice w/ Winifred Lenihan (1930)

Geraniums in My Window; a Comedy in Three Acts, w/ Samuel Ornitz (1934)

June 13; a Mystery-Drama in Three Acts, w/ Frank Vreeland (1940)

Wedding in Paris, w/ Sonny Miller (1956)

Laura, w/ George Sklar (1947)

Film Credits

Working Girls, (1931; play "Blind Mice")

The Night of June 13, (1932; story "Suburbs")

Private Scandal, (1934; story "In Conference")

Such Women Are Dangerous, (1934; story "Odd Thursday")

Hooray for Love, (1935; contributor to treatment; uncredited)

Party Wire, (1935; story; uncredited)

I'll Love You Always, (1935; writer)

Easy Living, (1937; story)

Scandal Street, (1938; story "Suburbs")

Service de Luxe, (1938; story)

Sing, Dance, Plenty Hot, (1940; story)

Lady from Louisiana, (1941; screenplay)

Lady Bodyguard, (1943; story)

Laura, (1944; novel)

Claudia and David, (1946; adaptation)

Bedelia, (1946; novel; screenplay)

Out of the Blue, (1947; story)

A Letter to Three Wives, (1949; adaptation)

I Can Get It for You Wholesale, (1951; adaptation)

Three Husbands, (1951; screenplay; story)

Give a Girl a Break, (1953; story)

The Blue Gardenia, (1953; story)

The 20th Century Fox Hour, (1955; episodes)

Les Girls, (1957; story)

Bachelor in Paradise, (1961; story)

Laura, (1962; TV; writer)

Laura, (1968; TV; novel)